THE CNT’S GOALS WITH THE NEW IWA

AMOR Y RABIA: The CNT’s agreement from the XI Congress makes it very clear that for the CNT, the anarcho-syndicalist movement “must base itself on local work (…) International solidarity arises as an extension of this work.” This can be seen as a clear position against the typical problem of the groups that form part of an organization when it’s time to mark out the specific areas of coordination to make sure that nobody’s local activities are affected. But it could also be understood as saying that international action is secondary, ignoring the complexity that is implied by coordinating our work at an international level, something very different from local activities.

As such, it would continue the attitude that is part of the problem, which in the past led to tolerating the current system of decision making in the IWA [International Workers Association], while sections without any real existence were accepted and given the same rights in decision-making as the sections with a real existence, which ended up as a minority. At the same time, the agreement from the XI Congress speaks of creating “an International of revolutionary unionism”, a description which is both broad and diffuse in its definition. Does the CNT have a strategic vision of international action? Or does it just have a tactical vision, centered in supporting local activities?

CNT International Secretary: We believe that the declaration about “the local” comes in relation to the miniscule groups in some countries, which, before they have a strategy to plant themselves and grow as an IWA Section in their country, come to integrate themselves into the structure, attracted by the initials, by a sense of belonging, or whatever it is. We believe that this false preoccupation with the international when there is no local cement is what contributes to them acting more like political control groups than like sections of the same International. If we achieve even a minimally acceptable local development of the sections, we believe that then there will be a real basis for thinking of international strategies that aren’t pure pie in the sky. In the CNT – and I believe in the other sections – nobody is thinking of abandoning the process that we are immersed in, in order to stick to just occasional support for local struggles. That wouldn’t make any sense. It’s another thing to be able to read the international situation correctly and, with the correct analysis, carry out successful actions. We’ll see what we’re capable of.

THE EXTINCTION OF ANARCHO-SYNDICALISM?

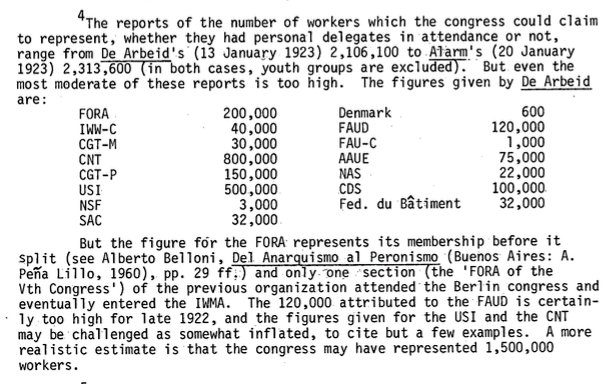

AMOR Y RABIA: A glance at the past shows that the IWA only existed as a real organization during the inter-war period (1922-1930), when it had strong and active sections, and an international activity. The creation of the IWA could be classified as a swan song for the international anarcho-syndicalist movement, since it collapsed shortly after it was founded. Fascism’s rise to power in Italy ended the USI, just as Salazar’s coup ended the Portuguese CGT, which up to that point was the main union in the country.[iv] Internal struggles put an end to the Argentine FORA, which reached a point of having two daily newspapers, the rise of Bolshevism destroyed French anarcho-syndicalism, and the flood of new members into the German FAUD after WW1 was followed by the sudden and fatal collapse once the economic situation stabilized, in the mid-1920s.

The illegalization of the CNT during the “soft dictatorship” [Dictablanda] of Primo de Rivera allowed the CNT to preserve itself like a mammoth in Siberian ice, making its resurrection in 1930/31 possible, but by this point the only organization with real influence that remained in the IWA was the Swedish SAC.[v] In practical terms, anarcho-syndicalism disappeared after the defeat of the CNT in the Spanish Civil War/Revolution and the decision of the SAC to move towards reformism after the Second World War. This is how, after the SAC’s exit, the IWA ended up as just the last name of the CNT in French exile, and its insignificance is made clear by the total lack of interest in its past. Today, the only well-documented history of the IWA is “The Unknown International”, by Vadim Damier, two volumes of 1600 pages (Vol 1: 1918-1930, Vol 2: 1930-1939). It’s symptomatic that it was written and published in Russia, a country where the IWA has never had even a minimal influence, and that nobody has taken on translating this into a language which the majority of the IWA can read.

The collapse of Communism and the Franco dictatorship allowed the CNT to revive itself, and the IWA with it. Sections which merit the name have popped up, but we’ve never successfully developed a truly international activity. The weakness of the new sections, and their “infantile disorders” which resulted from the contradictions inherent in trying to put 1930’s theory into practice in countries where neoliberalism ruled, quickly gave place to splits in Spain, France, and Italy. This turned the revived IWA into a cricket cage, incapable of offering a real perspective to any organizations that showed interest. Keeping all of this in mind, does anarcho-syndicalism still make sense on an international scale? Is it a real movement, or just a fossil from a bygone age? Is belonging to the IWA – or the very idea of international action itself – anything more than mere posturing?

CNT International Secretary: From our point of view, it makes complete sense. In recent years we’ve seen an increasing process of conglomeration, creating more multinationals at the expense of small and medium capitalism. We’ve had a bunch of conflicts where our sections have been able to count on the solidarity of workers beyond their borders, where their company or a company in the same group is established internationally. The new ease of communication, transport, and movement for capital (at the same time that restrictions against the movement of people are being hardened) has allowed many more capitalists to realize that the entire world is their playground. So it makes even more sense to organize internationally, not less.

The analysis of the historic process which you make – despite any possible clarifications that could be made, or a couple of errors – is essentially correct. The one-two punch of Fascism and Bolshevism led to a hard defeat of anarchist or libertarian ideas (not just anarcho-syndicalism) on the world scale during the ‘20s and ‘30s, so that after WW2 it was impossible to recover the previous strength. The “rebirths” from time to time of anarchist ideas and the anarcho-syndicalist project (Paris 1968, Spain after 1975, the UK in 1977, globally beginning in 1999, etcetera) have only complicated the situation, given the conditions in which they occurred. Nevertheless, we find ourselves in an opportune moment, when the changes in political culture over recent decades have put anarchist ideas in general back into the spotlight.

Thirty years ago, many people assumed that the Leninist-style democratic centralism was a natural and unquestionable form of organization. Now they prefer general assemblies and consensus. Of course, there’s a lot to say about this, and this isn’t the right outlet, but we do want to stress that we consider anarchist ideas, and the anarcho-syndicalist model, as tools of the future, not relics of the past. This does pose a serious challenge for anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists. We have to figure out how to adapt our strategies to the current situation, without renouncing one bit of our central and distinctive approaches (rejecting the state, avoiding institutional participation, direct action, mutual aid, etcetera). This is how we should look at the changes in focus that the CNT has applied to its workplace organizing in recent years. Some people don’t see a difference between questions of form and content, and they like to say the new strategic focus in our workplace organizing is a betrayal of principles, but this is completely wrong. On the contrary, it’s an effort to provide anarcho-syndicalism – and anarchist ideas by extension – with a present and future relevance that it has lacked in recent decades.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that we’ve figured it all out, nor that it’s going to be simple. We have to recognize that the current situation is very bad, and that overcoming it will require extraordinary effort. It’s significant that the IWA until now has not had a section in a country such as the US, with more than 300 million inhabitants (there was something symbolic more than 15 years ago which disappeared). So, the important thing isn’t a card with some initials (a question of form), but to provide it with meaning, with value, with concrete projects. The IWA is not a Platonic idea which exists perfectly somewhere, safe from the harm which we might do to it, as some people think. Anyone who is satisfied by the mere fact of “belonging” is fooling themselves, and in that case we can probably speak of posturing. It’s striking that many of those who are focusing on the Anselmo Lorenzo Foundation have never dropped in to give a hand, and that many of those who are tearing out their hair over the IWA never took on tasks or constructive proposals inside it, nor did they ever go to any of its meetings.[vi] The International will be what we make of it, all of us who are dedicated to working constructively inside it while struggling against an unjust social and economic system, until we overturn that system in a revolutionary process that won’t be led by any form of elites.

LIMITS

AMOR Y RABIA: Fighting against something is always easier than fighting for something. Creating something new requires an enormous amount of energy, which will doubtless be the case for the project of creating a new International of revolutionary unions. Until now, and despite limiting itself to the anarcho-syndicalist movement, the IWA which the CNT, USI, and FAU were active in was incapable of stopping the internal struggles of various sections (today there are 4 French CNT’s), establishing a satisfactory relationship with sympathetic but microscopic groups which have no real presence in their own countries, or establishing a clear boundary between anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism. To abandon the more or less clear terrain of “anarcho-syndicalism” for that of “revolutionary unionism” implies substituting a word with a precise meaning for one which is used by vary different organizations, from the IWW – which is an international organization in its own right – to the Italian “pure syndicalist” groups that followed Sorel’s ideas on violence and ended up supporting Mussolini.

The “Open invitation to the international conference of anarcho-syndicalist and revolutionary unionist organizations, Bilbao 26-27 November 2016” only listed a few requirements for becoming a part of the new International: Not having a vertical decision-making structure, not receiving state financing, not supporting political parties, and having more than 100 members. Does this mean that the CNT is in fact giving up on trying to form a purely anarcho-syndicalist international organization? What about, for example, union organizations with salaried staff? Or organizations that might be apolitical, nationalist, or even religious? Is it possible that there would be two sections in the same country, for example IWW and CNT? Where is the limit?

CNT International Secretary: I don’t think that by using the term “revolutionary unionism”, we’re giving up on the international that arises from this process identifying with anarcho-syndicalism. It’s possible that this term has been used in the past by totally erratic people as you describe, or to deliberately confuse people, but I also remember that the British once asked to be able to use another term such as this because “anarcho-syndicalism” sounds like an STD in their language, they told us, more than a revolutionary movement inspired by anarchism. There was not much debate on the topic.

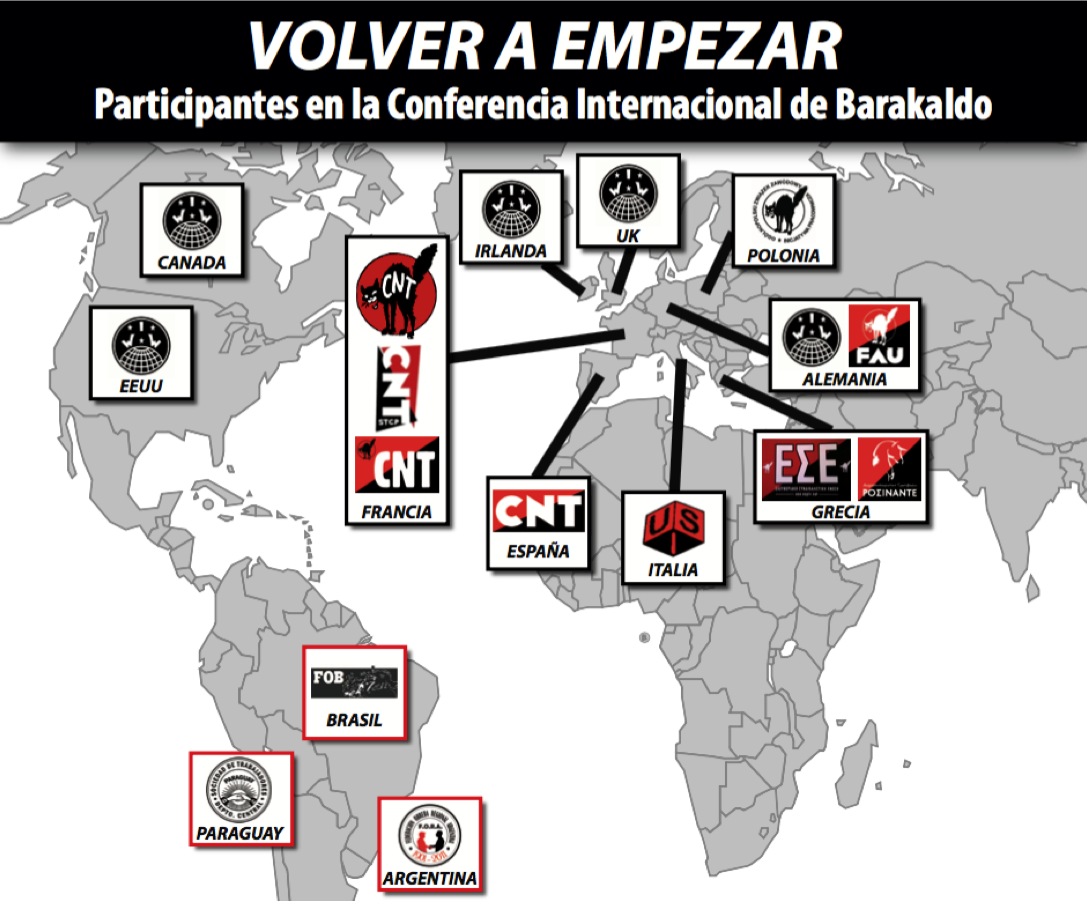

BACK TO THE BEGINNING: Participants in the International Conference in Barakaldo.

I believe that even more than the specific term which we adopt, we should be clear about our ideas, and, as we said before, what are the limits that we set to make sure that we progress without confusion towards a truly free society, without getting bogged down on the way. There’s been a lot of talk about salaried staff in organizations like this, and in general we reject them. It’s another things to use lawyers, or professionals when we are renovating our offices or doing technical installations, etc., when we have not been able to cover these kinds of work through volunteer labor from members.

None of the organizations which are trying to re-launch the international have any kind of paid staff. Similarly, we are sure that in the Congress which will be called, they will write up limits that no nationalist or religious organizations would be able to meet to be accepted. Not because we’re elitist, but because those ideas run against the same internationalism and anarchist vision of society which we have to construct through this tool.

We also imagine that there might be a discussion about the possibility of two or more sections existing in one country. In fact, it’s a proposal that’s been brought up by other unions and which the CNT will dedicate time to discussing and taking a position on. If it helps to smooth out some ruffled feathers, and to avoid a culture of division over who will be “the chosen one”, as we see in France with up to 5 unions which claim anarcho-syndicalist heritage – then it would be welcome. Although it still hasn’t been formally brought up within the CNT, it’s a proposal which some of the organizations interested in the process want to bring up, and which will have to be debated.

In any case, this brings us back to the last response, where we spoke of the risks in the process. There are many open questions which will have to be closed in order to be able to draw up an associative pact that works for all of the participating organizations, beginning with the proposals about membership, and which succeeds in capturing all of the aspects that we spoke about before. For this, we need time, effort, good will, and the right answers. We hope that we can pull it off.

EUROCENTRISM AND ISLAMOPHOBIA?

AMOR Y RABIA: For an international organization, projecting its activities and ideas throughout the world is fundamental. In this sense, the IWA has been a complete failure, with an undeniably Eurocentric character. Throughout recent decades, the IWA has been incapable of offering a space for the real union organizations from the countries of the so-called “third world” which have approached it, while it has had no problem at all bringing in groups from Western countries without any real workplace presence, or which, in some cases, were really just pure anarchist groups rather than anarcho-syndicalist ones. Nigeria, South Africa, Nepal and Bangladesh are some examples of lost opportunities.[vii]

On top of eurocentrism we have to add a certain Islamophobia, conscious or not. Despite the appearance for the first time of anarchist groups in the Arab world (Tunisia, Egypt) during the so-called “Arab Spring”, and the growing interest in anarchist ideas in Turkey, interest in the IWA in these countries is conspicuous by its absence. And the same is true with propaganda in other non-Western languages, such as Arabic, Chinese, or Hindi, mother tongues for the majority of the world’s population. Beyond big words, an international organization implies much more than just the solidarity with local struggles that the agreements from the XI CNT Congress speak of.

If an international organization wants to have a real existence, it has to be capable of bringing in groups from countries with very different social and economic structures. What approach do the CNT/USI/FAU, who pull together about 90% of the international membership of anarcho-syndicalist organizations, to attract or work with union organizations from the countries of the so-called “third world”, which are the majority of the world’s population? Is the CNT ready to support (and finance) a dynamic activity on the part of a new international?

CNT International Secretary: It’s true that we have lost opportunities for expansion for the international outside of Europe during this period of self-destruction of the international. We have to make sure we don’t repeat these mistakes in the living organization which we hope results from this whole process. In Nigeria contact was lost, but I remember the case of Bangladesh and the doubts that arose around the forms of functioning that we have in Europe. What we’re missing is a labor of empathy with the situations in countries like that, whose daily life couldn’t be more different. We have to stop gazing at our own navels, in an attitude that we learned from the colonialist accents of our own exploiters.

FIRST CONFERENCE OF THE EGYPTIAN LIBERTARIAN SOCIALIST MOVEMENT (November 7, 2011): The appearance of anarchism in Africa and in countries with Islamic culture forms part of the process of modernization of those societies.

I believe that if we start with cordial understanding and some minimum bases for living together in an organization, we can undertake some very fruitful work here, and I don’t have the slightest doubt that we’ll be able to integrate organizations of workers in Africa, Asia, and the Americas with whom we have much more in common than it might seem. We are sure that the first successes here will help to build a consciousness about how to tackle the following projects in countries which, in their level of economic development or of repression, have much more in common with each other than they might with the reality of Europe. The lack of real, dynamic activity in this and other fields is exactly what has led us to break with the current drift. We hope that in time we’ll be able to demonstrate that things should be done differently in order to attract those who are organized as workers in other countries to our principles, tactics, and aims, or to develop projects whose aim will be the creation of organizations that might become new sections.

However, we have to be conscious of our own size and our resources. We’ve already said that anarcho-syndicalism on a world scale is in a worrisome state and that it must be revitalized. The CNT, with all that it has, and despite being the largest anarcho-syndicalist organization in the world (that we know of) is infinitely smaller than we would like. That is to say, it doesn’t make sense to ask whether the CNT is ready to finance the international activity of other developing sections. To put the debate in these terms is unfair. What we can do is put effort into creating a climate of solidarity and comradeliness in international work, so that all of the organizations that we relate with feel like we have their backs, and so that they can all contribute as much as possible to the growth and recuperation of anarcho-syndicalism as a thriving movement on a world scale. We are convinced that for this, they can definitely count on close collaboration from us and from all of the organizations that get involved in this project.

_______________

[This interview was originally published in Spanish, in two parts. 1 and 2. English translation by Lifelong Wobbly.]

[i] The CNT suffered two splits in 1979 and 1983 which eventually became the CGT. The main issue was over participation in state-sponsored works councils, and state and employer subsidies tied to the councils. [This and all other footnotes are by the translator.]

[ii] I translate “sindicalismo revolucionario” as “revolutionary unionism” as this is a better English rendering than “revolutionary syndicalism”. However, “anarcosindicalismo” remains “anarcho-syndicalism.”

[iii] It is common for revolutionary unions in other countries to have a document of “Principles, tactics, and aims” which is updated at each Congress to reflect their living strategy.

[iv] The Italian USI had hundreds of thousands of members prior to Benito Mussolini’s fascist coup in 1922. The Portuguese military coup of 1926 gradually led to the corporatist state of Antonio Salazar, which lasted until the Carnation Revolution of 1974.

[v] “Dictablanda” is a pun on “dictadura” (dura = hard; blanda = weak) and is used to describe Miguel Primo de Rivera’s unstable dictatorship from 1923-1930, which ended with the abolition of the Monarchy and the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic.

[vi] Named after “the grandfather of Spanish anarchism” (in Murray Bookchin’s words), the Anselmo Lorenzo Foundation is a publishing house tied to the CNT, which also maintains the union’s extensive historical archives. They recently opened a space in Madrid and apparently they have been a target for criticism by the small number of IWA loyalists.

[vii] These are countries where unions have approached the IWA over the last 20 years or so. The National Garment Workers Federation in Bangladesh have also maintained contact with the IWW over the years.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario