Which is why the anarchist writer David Graeber, who died last year, was the black sheep of academic anthropology. As a popular and prolific assistant professor at Yale, he was thought to be a sure bet for tenure. But the department turned him down, with almost no explanation. It was universally assumed that Graeber’s anarchist principles, activist politics—especially his support for Yale graduate students trying to organize a union—and cheeky personality cost him the prize. (No doubt the department shuddered with relief at its near escape when he later became a leading interpreter and spokesman for Occupy Wall Street.) Offers from other departments trickled in—he ended up at the London School of Economics—and the huge success of his Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011) must also have assuaged the bitterness. But the lesson had been delivered: Outspokenness was not costless. Outspokenness, however, was instinctive with Graeber, as was his extraordinary generosity to students and younger colleagues, who responded with extraordinary affection, even love.

His final book, The Dawn of Everything, a co-written study of the earliest forms of social organization, caps a large and variegated output. Debt, controversial but enormously erudite and startlingly original, was his best-known work, though his two explicitly political volumes were also bestsellers: The Democracy Project (2013), a chronicle of Occupy Wall Street, followed by a scathing critique of American society and politics; and Bullshit Jobs (2018), an acerbic history and analysis of pointless drudgery (an important theme in The Dawn of Everything as well). The Utopia of Rules (2015) gathered several celebrated essays, including “The Utopia of Rules, or Why We Really Love Bureaucracy After All” and “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit.” He was on quite a roll in his last decade. But the above was not all he was doing.

In a moving foreword to The Dawn of Everything, Graeber’s co-author, David Wengrow, an archaeology professor at University College London, described their 10-year collaboration on “a new history of humankind”: a period when “it was not uncommon for us to talk two or three times a day. We would often lose track of who came up with what idea or which new set of facts and examples.… We got to the end just as we’d started, in dialogue, with drafts passing constantly back and forth between us as we read, shared and discussed the same sources, often into the small hours of the night.” It sounds idyllic—a form of collaboration much like those that he and Wengrow argue underpinned some of the earliest human societies.

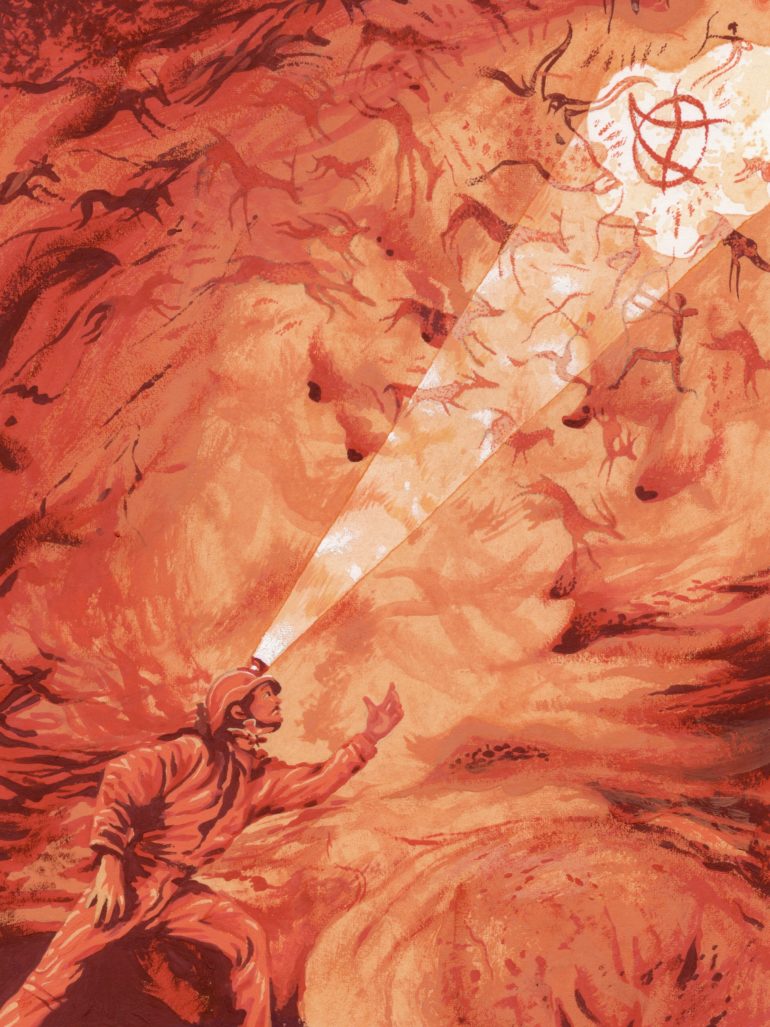

There is a Standard Version of deep history, those long ages before writing (roughly 40,000–12,000 B.C.E.), when humans left behind traces—suggestive but not definitive—of culture and technology. The Standard Version is a species of technological determinism, in which forms of society correspond to modes of production. There have been four main social forms, according to this theory: bands, mobile groups of a few families; tribes, of perhaps 100 members, moving a few times a year; chiefdoms, hundreds strong, centered in one place but with smaller groups occasionally moving away for various reasons; and states, with thousands of members, centered in cities, and with a central government more or (usually) less accountable to the populace. To each of these forms corresponded a mode of subsistence: respectively, hunting/gathering; gardening/foraging/herding; farming; and industry. Political forms followed a closely parallel evolution: egalitarianism, private property, kingship (often just ceremonial), and the bureaucratic state. Each of these stages was more productive and more civilized than the last, but also less equal and less free.

In addition to its pleasing symmetry, the Standard Version has a certain pathos that appeals to supposedly tough-minded scientists. Civilization is a stern fate, on this view: We can only attain modernity’s deepest satisfactions by giving up the mobility, spontaneity, and nonchalance of our free-spirited but immature ancestors. We moderns—and especially intellectuals, who grasp this painful dilemma most fully—become tragic heroes of a sort.

Graeber and Wengrow, however, are intent on blowing up the Standard Version in The Dawn of Everything. It was an understandable attempt to extrapolate from very limited data (and, in some cases, a less excusable attempt to retroactively justify Western colonialism). But in the last few decades, a mass of new evidence from archaeology and anthropology has appeared, leaving it all but unsalvageable. Again and again, among the Kwakiutl, Nambikwara, Inuit, Lakota, and innumerable others, from the Amazon to the Arctic Circle to Central Africa to the Great Plains, and in all periods from the Upper Paleolithic to the nineteenth century, archaeologists have discovered variety where the Standard Version predicted uniformity.

Until around 10,000 B.C., according to the eminent primatologist Christopher Boehm, articulating the scholarly consensus, humans lived in “societies of equals, and outside the family there were no dominators.” In such societies, where supposedly no distinctions of power or rank were observed in life, it seems unlikely they would have been observed in death. They were, however, and regularly. Rich burials—in unusually large graves or with ornaments, tools, textiles, or weapons, sometimes in profusion—have been found on every continent, often dating to millennia before social distinctions of any sort were supposed to have arisen in human societies. The egalitarian bands of prehistory, never solidly based on evidence, may soon disappear into myth.

Monumental architecture is more evidence against the standard evolutionary scheme. In southern Turkey, for example, there is an ensemble of 20 stone temples, about as large as Stonehenge (which dates from 3000 B.C.), with carved portraits of animals on the pillars. It dates from 9000 B.C. In Poverty Point, Louisiana, a network of enormous mounds and ridges stretches out across 400 acres or so. Constructed in 1600 B.C. (by moving a million cubic meters of earth), it may have been a trading center or a ritual center. Its builders seem to have been hunters, fishers, and foragers. Across Eastern Europe is a line of “mammoth houses,” enclosures up to 40 feet in diameter made of mammoth hides stretched over poles, constructed between 25,000 and 12,000 years ago, obviously by at least part-time hunters. Every year, more very old monuments constructed by nonfarming, non-state people are discovered, making it harder to believe that such achievements are only possible, as the conventional wisdom has it, on the basis of agricultural surpluses and bureaucratic expertise.

Evidence of occupational variety at many sites calls for explanation: It seems unlikely that, at the same moment in a given area, one group consisted of full-time agriculturalists, another of full-time foragers, and another full-time pastoralists. It now appears that seasonality was very common, with groups changing not only their way of procuring food one or more times a year, but authority relations and other customs as well. Members of a North American Plains tribe, for example, were foragers and herders for most of the year, with very lax discipline both at home and toward tribal leaders. During the great annual buffalo hunt, however, the tribe became quite hierarchical; in particular, there were “buffalo police” who enforced norms of cooperation and distribution very strictly and even had the power to impose capital punishment on the spot for sufficiently grave violations. Most indigenous Amazonian societies had different authority structures at different times of year. Perhaps the best-known example is from the Arctic, where Inuit fathers exercised strict patriarchal authority in summer, while winter, lived more inside, was something of a saturnalia, with spouse-swapping and children running free.

By and large, anthropologists have not made much of seasonality. (Interestingly, most of those who have done so have been anarchist-leaning: Marcel Mauss, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Robert Lowie, Pierre Clastres.) Graeber and Wengrow make a great deal of it.

His final book, The Dawn of Everything, a co-written study of the earliest forms of social organization, caps a large and variegated output. Debt, controversial but enormously erudite and startlingly original, was his best-known work, though his two explicitly political volumes were also bestsellers: The Democracy Project (2013), a chronicle of Occupy Wall Street, followed by a scathing critique of American society and politics; and Bullshit Jobs (2018), an acerbic history and analysis of pointless drudgery (an important theme in The Dawn of Everything as well). The Utopia of Rules (2015) gathered several celebrated essays, including “The Utopia of Rules, or Why We Really Love Bureaucracy After All” and “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit.” He was on quite a roll in his last decade. But the above was not all he was doing.

In a moving foreword to The Dawn of Everything, Graeber’s co-author, David Wengrow, an archaeology professor at University College London, described their 10-year collaboration on “a new history of humankind”: a period when “it was not uncommon for us to talk two or three times a day. We would often lose track of who came up with what idea or which new set of facts and examples.… We got to the end just as we’d started, in dialogue, with drafts passing constantly back and forth between us as we read, shared and discussed the same sources, often into the small hours of the night.” It sounds idyllic—a form of collaboration much like those that he and Wengrow argue underpinned some of the earliest human societies.

There is a Standard Version of deep history, those long ages before writing (roughly 40,000–12,000 B.C.E.), when humans left behind traces—suggestive but not definitive—of culture and technology. The Standard Version is a species of technological determinism, in which forms of society correspond to modes of production. There have been four main social forms, according to this theory: bands, mobile groups of a few families; tribes, of perhaps 100 members, moving a few times a year; chiefdoms, hundreds strong, centered in one place but with smaller groups occasionally moving away for various reasons; and states, with thousands of members, centered in cities, and with a central government more or (usually) less accountable to the populace. To each of these forms corresponded a mode of subsistence: respectively, hunting/gathering; gardening/foraging/herding; farming; and industry. Political forms followed a closely parallel evolution: egalitarianism, private property, kingship (often just ceremonial), and the bureaucratic state. Each of these stages was more productive and more civilized than the last, but also less equal and less free.

In addition to its pleasing symmetry, the Standard Version has a certain pathos that appeals to supposedly tough-minded scientists. Civilization is a stern fate, on this view: We can only attain modernity’s deepest satisfactions by giving up the mobility, spontaneity, and nonchalance of our free-spirited but immature ancestors. We moderns—and especially intellectuals, who grasp this painful dilemma most fully—become tragic heroes of a sort.

Graeber and Wengrow, however, are intent on blowing up the Standard Version in The Dawn of Everything. It was an understandable attempt to extrapolate from very limited data (and, in some cases, a less excusable attempt to retroactively justify Western colonialism). But in the last few decades, a mass of new evidence from archaeology and anthropology has appeared, leaving it all but unsalvageable. Again and again, among the Kwakiutl, Nambikwara, Inuit, Lakota, and innumerable others, from the Amazon to the Arctic Circle to Central Africa to the Great Plains, and in all periods from the Upper Paleolithic to the nineteenth century, archaeologists have discovered variety where the Standard Version predicted uniformity.

Until around 10,000 B.C., according to the eminent primatologist Christopher Boehm, articulating the scholarly consensus, humans lived in “societies of equals, and outside the family there were no dominators.” In such societies, where supposedly no distinctions of power or rank were observed in life, it seems unlikely they would have been observed in death. They were, however, and regularly. Rich burials—in unusually large graves or with ornaments, tools, textiles, or weapons, sometimes in profusion—have been found on every continent, often dating to millennia before social distinctions of any sort were supposed to have arisen in human societies. The egalitarian bands of prehistory, never solidly based on evidence, may soon disappear into myth.

Monumental architecture is more evidence against the standard evolutionary scheme. In southern Turkey, for example, there is an ensemble of 20 stone temples, about as large as Stonehenge (which dates from 3000 B.C.), with carved portraits of animals on the pillars. It dates from 9000 B.C. In Poverty Point, Louisiana, a network of enormous mounds and ridges stretches out across 400 acres or so. Constructed in 1600 B.C. (by moving a million cubic meters of earth), it may have been a trading center or a ritual center. Its builders seem to have been hunters, fishers, and foragers. Across Eastern Europe is a line of “mammoth houses,” enclosures up to 40 feet in diameter made of mammoth hides stretched over poles, constructed between 25,000 and 12,000 years ago, obviously by at least part-time hunters. Every year, more very old monuments constructed by nonfarming, non-state people are discovered, making it harder to believe that such achievements are only possible, as the conventional wisdom has it, on the basis of agricultural surpluses and bureaucratic expertise.

Evidence of occupational variety at many sites calls for explanation: It seems unlikely that, at the same moment in a given area, one group consisted of full-time agriculturalists, another of full-time foragers, and another full-time pastoralists. It now appears that seasonality was very common, with groups changing not only their way of procuring food one or more times a year, but authority relations and other customs as well. Members of a North American Plains tribe, for example, were foragers and herders for most of the year, with very lax discipline both at home and toward tribal leaders. During the great annual buffalo hunt, however, the tribe became quite hierarchical; in particular, there were “buffalo police” who enforced norms of cooperation and distribution very strictly and even had the power to impose capital punishment on the spot for sufficiently grave violations. Most indigenous Amazonian societies had different authority structures at different times of year. Perhaps the best-known example is from the Arctic, where Inuit fathers exercised strict patriarchal authority in summer, while winter, lived more inside, was something of a saturnalia, with spouse-swapping and children running free.

By and large, anthropologists have not made much of seasonality. (Interestingly, most of those who have done so have been anarchist-leaning: Marcel Mauss, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Robert Lowie, Pierre Clastres.) Graeber and Wengrow make a great deal of it.

Archaeological evidence ... suggests that in the highly seasonal environments of the last Ice Age, our remote ancestors ... shifted back and forth between alternative social arrangements, allowing the rise of authoritarian structures during certain times of year. The same individual could experience life in what looks to us sometimes like a band, sometimes a tribe, and sometimes like something with at least some of the characteristics we now identify with states. With such institutional flexibility comes the capacity to step outside the boundaries of any given structure and reflect; to both make and unmake the political worlds we live in.

It is difficult for some—perhaps most—of us to attribute so advanced a political and philosophical consciousness to our remote ancestors. Perhaps, Graeber and Wengrow suggest, that is the problem: Our unshakable conviction that modernity spells progress and liberation prevents us from seeing that, in many times and places, premodern life was actually more rational and free.

Though combative, The Dawn of Everything is an upbeat book. Its debunking energies mainly go to refuting the conventional wisdom at its most discouraging. For example, anthropologists and archaeologists (like most everyone else) tend to assume there is an inverse relation between scale and equality; that the greater the number of people who need to be organized to work or live or fight together, the more coercion will be necessary. Cities represent a scaling up of population, and therefore, naturally, of mechanisms of control. And where did cities come from?

The conventional story looks for the ultimate causes in technological factors: Cities were a delayed, but inevitable, effect of the “Agricultural Revolution,” which started populations on an upward trajectory, and set off a chain of other developments, for instance in transport and administration, which made it possible to support large populations living in one place. These large populations then required states to administer them.

This conventional story is being undermined by new archaeological evidence, especially from the largest prehistoric cities, in Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica. Those “large populations living in one place”—peasantries—do not show up until later in the histories of most large cities. Initially, besides farmers drawn to a fertile floodplain, there were equal numbers of hunters, foragers, and fishers, and sometimes very large ceremonial or ritual centers. What there don’t seem to have been, by and large, were ruling classes. The conventional assumption—amounting almost to a Weltanschauung—that civilization marches in lockstep with state authority seems to be tottering.

The Agricultural Revolution is another key element of the Standard Version: a swift and mostly complete transition from mobile, egalitarian, healthy foragers, relatively few in number, lacking the concept of private property, and living on wild resources, to farming populations, numerous, sedentary, class-stratified, disease-ridden, and producing a surplus of food. The consequence, as noted above, was cities, and the inevitable concomitant of cities was states. But this turns out to be far too neat. As recent evidence shows, many populations took up farming and then went back to foraging. Many foraging communities were far more authoritarian than farming communities. And in quite a few places, the transition from foraging to farming took thousands of years. It may be necessary to rechristen the Agricultural Revolution as the Agricultural Slow Walk.

Prehistory, Graeber and Wengrow insist, is vastly more interesting than scholars knew until recently. And not just more interesting, but more inspiring as well: “It is clear now that human societies before the advent of farming were not confined to small, egalitarian bands. On the contrary, the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of several bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms, far more than it does the drab abstractions of evolutionary theory.” “Carnival” brings to mind Occupy, which, along with this book, testifies to David Graeber’s admirable energy, imagination, and love of freedom.

For all its historical and theoretical brilliance, The Dawn of Everything does not wholly vindicate the anarchist philosophical framework in which the argument is set. Graeber and Wengrow do not exactly preach anarchism, but the moral of their long and immensely rich study is clear: Relations of authority are the most important and revealing things about any society, small or large, and no one should ever be subject to any authority she hasn’t chosen to be subject to.

Who could disagree—as long as it’s understood that accepting citizenship in a democratic polity means choosing to be subject to its authority? This is a window on a long-standing quarrel between anarchists and their less glamorous political cousins, socialists and social democrats. As one of the latter tribe, I confess that The Dawn of Everything did get a rise out of me now and then. For one thing, nearly everyone to the left of Genghis Khan has a sentimental fondness for the European Enlightenment—it’s where the critical spirit found its voice. Graeber and Wengrow think it’s vastly overrated. Enlightenment thinkers weren’t particularly original, they write; their political ideas came mostly from China and from Native Americans. The proof is that Leibniz and Montesquieu praised the Chinese civil service and recommended it to European rulers while Native Americans who visited Europe impressed the philosophers so much that many of them put the visitors into their philosophical dialogues.

Native American political thought is certainly impressive, and Graeber and Wengrow expound it superlatively well. Still, no one has claimed (as far as I know) that Europe got from Native Americans the ideas of habeas corpus, an independent judiciary, trial by jury, a free press, religious disestablishment, or a written constitution with enumerated rights; or that Adam Smith got from them the idea of labor unions, free education for workers, or income redistribution, all of which he argued for in The Wealth of Nations (though few conservatives have noticed). Perhaps the American left should take a break from trying to subvert the Enlightenment until the American right stops trying to roll it back.

Graeber and Wengrow’s second foray into socialist-/social democrat–baiting is more surprising. Equality, the cherished ideal of most leftists past and present, seems to them a theoretical and strategic dead end, a mere “technocratic” reform. They dismiss, even mock, equality as a goal:

To create a society of true equality today, you’re going to have to figure out a way to go back to becoming tiny bands of foragers again with no significant personal property. Since foragers require a pretty extensive territory to forage in, this would mean having to reduce the world’s population by something like 99.9 percent. Otherwise, the best we can hope for is to adjust the size of the boot that will forever be stomping on our faces; or, perhaps, to wrangle a bit more wiggle room in which some of us can temporarily duck out of its way.

Equality is not only an unworthy goal; it is not even an intelligible one: “it remains entirely unclear what ‘egalitarian’ even means.” Does it? It seems clear enough to me: a society with a Gini coefficient below 0.2 (Graeber and Wengrow persistently and annoyingly disparage the Gini coefficient, our best quantitative measure of inequality); universal free health care; universal free preschool and public higher education; equal per-pupil expenditures in primary and secondary school; a Universal Basic Income (maybe); enforcement of labor law (the nonenforcement of which has destroyed American unionism); enforcement of tax law (the nonenforcement of which is a trillion-dollar annual gift to the wealthy); all adult citizens automatically registered to vote; exclusively public funding of elections; transparency mechanisms, including a vastly expanded Freedom of Information Act; and accountability mechanisms, including recall, at all levels. If that’s not an egalitarian program, why not? And if Graeber and Wengrow wouldn’t regard it as well worth fighting for, why not?

I think I know why: Because, unlike in grubby, soulless social democracy, people in true communism (for example, the indigenous societies of the Northeast Woodlands before the European invasion) “guaranteed one another the means to an autonomous life—or at least ensured no man or woman was subordinated to any other.” That is the anarchist ideal. Well, what is the purpose of the socialist/social democratic reforms I just proposed except to guarantee everyone “the means to an autonomous life” in an industrial society? “Industrial society”—there’s the rub. Is anarchism feasible in a society of any considerable size or complexity, where coordination, authority, and expertise are essential? How much of mass production, technological innovation, cheap paperbacks and CDs, and the rest of our accursedly seductive late-capitalist way of life do we want to walk back? And how do we do that without starving or stranding or inciting to rebellion the hundreds of millions of hapless humans trapped into dependence on cars, air travel, supermarkets, and single-family houses? Few contemporary anarchist writers have addressed these questions squarely, and none satisfactorily.

Still, socialists and social democrats have a very large blind spot of our own: the ideology of progress. Believing that democracy and technology advance together, that representative institutions and scientific rationality will reliably and permanently vanquish ignorance and want, and that the historical record demonstrates all this, we can’t account for historical regression (like contemporary right-wing populism in Europe and the United States) or precocity—outstanding political virtue or imagination among peoples with few material attainments. Anarchists, free of this intellectual baggage, need not tie themselves in knots to explain these “paradoxes” of progress.

Labels, clearly, are an aid to misunderstanding. Surely it is not necessary to choose between freedom and equality, much less to disparage those who make the opposite choice. If an anarchist believes in freedom, and a socialist believes in equality, what is someone who believes in freedom and equality? A wise person and a useful citizen.

It is difficult for some—perhaps most—of us to attribute so advanced a political and philosophical consciousness to our remote ancestors. Perhaps, Graeber and Wengrow suggest, that is the problem: Our unshakable conviction that modernity spells progress and liberation prevents us from seeing that, in many times and places, premodern life was actually more rational and free.

Though combative, The Dawn of Everything is an upbeat book. Its debunking energies mainly go to refuting the conventional wisdom at its most discouraging. For example, anthropologists and archaeologists (like most everyone else) tend to assume there is an inverse relation between scale and equality; that the greater the number of people who need to be organized to work or live or fight together, the more coercion will be necessary. Cities represent a scaling up of population, and therefore, naturally, of mechanisms of control. And where did cities come from?

The conventional story looks for the ultimate causes in technological factors: Cities were a delayed, but inevitable, effect of the “Agricultural Revolution,” which started populations on an upward trajectory, and set off a chain of other developments, for instance in transport and administration, which made it possible to support large populations living in one place. These large populations then required states to administer them.

This conventional story is being undermined by new archaeological evidence, especially from the largest prehistoric cities, in Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica. Those “large populations living in one place”—peasantries—do not show up until later in the histories of most large cities. Initially, besides farmers drawn to a fertile floodplain, there were equal numbers of hunters, foragers, and fishers, and sometimes very large ceremonial or ritual centers. What there don’t seem to have been, by and large, were ruling classes. The conventional assumption—amounting almost to a Weltanschauung—that civilization marches in lockstep with state authority seems to be tottering.

The Agricultural Revolution is another key element of the Standard Version: a swift and mostly complete transition from mobile, egalitarian, healthy foragers, relatively few in number, lacking the concept of private property, and living on wild resources, to farming populations, numerous, sedentary, class-stratified, disease-ridden, and producing a surplus of food. The consequence, as noted above, was cities, and the inevitable concomitant of cities was states. But this turns out to be far too neat. As recent evidence shows, many populations took up farming and then went back to foraging. Many foraging communities were far more authoritarian than farming communities. And in quite a few places, the transition from foraging to farming took thousands of years. It may be necessary to rechristen the Agricultural Revolution as the Agricultural Slow Walk.

Prehistory, Graeber and Wengrow insist, is vastly more interesting than scholars knew until recently. And not just more interesting, but more inspiring as well: “It is clear now that human societies before the advent of farming were not confined to small, egalitarian bands. On the contrary, the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of several bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms, far more than it does the drab abstractions of evolutionary theory.” “Carnival” brings to mind Occupy, which, along with this book, testifies to David Graeber’s admirable energy, imagination, and love of freedom.

For all its historical and theoretical brilliance, The Dawn of Everything does not wholly vindicate the anarchist philosophical framework in which the argument is set. Graeber and Wengrow do not exactly preach anarchism, but the moral of their long and immensely rich study is clear: Relations of authority are the most important and revealing things about any society, small or large, and no one should ever be subject to any authority she hasn’t chosen to be subject to.

Who could disagree—as long as it’s understood that accepting citizenship in a democratic polity means choosing to be subject to its authority? This is a window on a long-standing quarrel between anarchists and their less glamorous political cousins, socialists and social democrats. As one of the latter tribe, I confess that The Dawn of Everything did get a rise out of me now and then. For one thing, nearly everyone to the left of Genghis Khan has a sentimental fondness for the European Enlightenment—it’s where the critical spirit found its voice. Graeber and Wengrow think it’s vastly overrated. Enlightenment thinkers weren’t particularly original, they write; their political ideas came mostly from China and from Native Americans. The proof is that Leibniz and Montesquieu praised the Chinese civil service and recommended it to European rulers while Native Americans who visited Europe impressed the philosophers so much that many of them put the visitors into their philosophical dialogues.

Native American political thought is certainly impressive, and Graeber and Wengrow expound it superlatively well. Still, no one has claimed (as far as I know) that Europe got from Native Americans the ideas of habeas corpus, an independent judiciary, trial by jury, a free press, religious disestablishment, or a written constitution with enumerated rights; or that Adam Smith got from them the idea of labor unions, free education for workers, or income redistribution, all of which he argued for in The Wealth of Nations (though few conservatives have noticed). Perhaps the American left should take a break from trying to subvert the Enlightenment until the American right stops trying to roll it back.

Graeber and Wengrow’s second foray into socialist-/social democrat–baiting is more surprising. Equality, the cherished ideal of most leftists past and present, seems to them a theoretical and strategic dead end, a mere “technocratic” reform. They dismiss, even mock, equality as a goal:

To create a society of true equality today, you’re going to have to figure out a way to go back to becoming tiny bands of foragers again with no significant personal property. Since foragers require a pretty extensive territory to forage in, this would mean having to reduce the world’s population by something like 99.9 percent. Otherwise, the best we can hope for is to adjust the size of the boot that will forever be stomping on our faces; or, perhaps, to wrangle a bit more wiggle room in which some of us can temporarily duck out of its way.

Equality is not only an unworthy goal; it is not even an intelligible one: “it remains entirely unclear what ‘egalitarian’ even means.” Does it? It seems clear enough to me: a society with a Gini coefficient below 0.2 (Graeber and Wengrow persistently and annoyingly disparage the Gini coefficient, our best quantitative measure of inequality); universal free health care; universal free preschool and public higher education; equal per-pupil expenditures in primary and secondary school; a Universal Basic Income (maybe); enforcement of labor law (the nonenforcement of which has destroyed American unionism); enforcement of tax law (the nonenforcement of which is a trillion-dollar annual gift to the wealthy); all adult citizens automatically registered to vote; exclusively public funding of elections; transparency mechanisms, including a vastly expanded Freedom of Information Act; and accountability mechanisms, including recall, at all levels. If that’s not an egalitarian program, why not? And if Graeber and Wengrow wouldn’t regard it as well worth fighting for, why not?

I think I know why: Because, unlike in grubby, soulless social democracy, people in true communism (for example, the indigenous societies of the Northeast Woodlands before the European invasion) “guaranteed one another the means to an autonomous life—or at least ensured no man or woman was subordinated to any other.” That is the anarchist ideal. Well, what is the purpose of the socialist/social democratic reforms I just proposed except to guarantee everyone “the means to an autonomous life” in an industrial society? “Industrial society”—there’s the rub. Is anarchism feasible in a society of any considerable size or complexity, where coordination, authority, and expertise are essential? How much of mass production, technological innovation, cheap paperbacks and CDs, and the rest of our accursedly seductive late-capitalist way of life do we want to walk back? And how do we do that without starving or stranding or inciting to rebellion the hundreds of millions of hapless humans trapped into dependence on cars, air travel, supermarkets, and single-family houses? Few contemporary anarchist writers have addressed these questions squarely, and none satisfactorily.

Still, socialists and social democrats have a very large blind spot of our own: the ideology of progress. Believing that democracy and technology advance together, that representative institutions and scientific rationality will reliably and permanently vanquish ignorance and want, and that the historical record demonstrates all this, we can’t account for historical regression (like contemporary right-wing populism in Europe and the United States) or precocity—outstanding political virtue or imagination among peoples with few material attainments. Anarchists, free of this intellectual baggage, need not tie themselves in knots to explain these “paradoxes” of progress.

Labels, clearly, are an aid to misunderstanding. Surely it is not necessary to choose between freedom and equality, much less to disparage those who make the opposite choice. If an anarchist believes in freedom, and a socialist believes in equality, what is someone who believes in freedom and equality? A wise person and a useful citizen.