By Adam Ramsay

The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. This audacious claim was made by the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard in March 1991, only two months after NATO forces had rained explosives on Iraq, shedding the blood of more than a hundred thousand people.

To understand Cambridge Analytica and its parent firm, Strategic Communication Laboratories, we need to get our heads round what Baudrillard meant, and what has happened since: how military propaganda has changed with technology, how war has been privatised, and how imperialism is coming home.

Baudrillard’s argument centred on the fact that NATO’s action in the Gulf was the first time audiences in Western countries had been able to watch a war live, on rolling TV news – CNN had become the first 24-hour news channel in 1980. Because camera crews were embedded with American troops, by whom they were effectively censored, the coverage had little resemblance to the reality of the bombardment of Iraq and Kuwait. The events known to Western audiences as “The Gulf War” – symbolised by camera footage from ‘precision’ missiles and footage of military hardware – are more accurately understood as a movie directed from the Pentagon. They were so removed from the gore-splattered reality that it’s an abuse of language to call them the same thing. Hence, the “Gulf War” did not take place.

Watch | Desert Storm’s First Apache Strikes

Not long after Baudrillard’s iconic essay was published, Strategic Communications Laboratories was founded. “SCL Group provides data, analytics and strategy to governments and military organisations worldwide” reads the first line of its website. “For over 25 years, we have conducted behavioural change programmes in over 60 countries & have been formally recognised for our work in defence and social change.”

Of course, military propaganda was nothing new. And nor is the extent to which it has evolved alongside changes in media technology and economics. The film Citizen Kane tells a fictionalised version of the first tabloid (or, as Americans call it, ‘yellow journalism’) war: how the circulation battle between William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World arguably drove the US into the 1889 Spanish American War. It was during this affair that Hearst reportedly told his correspondent, “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war”, as parodied in Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop. But after the propaganda disaster of the Tet offensive in Vietnam softened domestic support for the war, the military planners began to devise new ways to control media reporting.

As a result, when Britain went to war with Argentina over the Falklands in 1982, they pioneered a new technique for media control: embedding journalists with troops. And, as former BBC war reporter Caroline Wyatt blogged, “The lessons from embedding journalists with the Royal Navy during the Falklands war were taken up enthusiastically by military planners in both Washington and London for the First Gulf War in 1991.”

The UK defence secretary during the Falklands War when the use of embedded journalists was pioneered was John Nott (who backed Brexit). As my colleague Caroline Molloy pointed out to me, his son-in-law is Tory MP Hugo Swire, former minister in both the Northern Ireland Office and the Foreign Office. Swire’s cousin – with whom he overlapped at Eton – is Nigel Oakes, founder of Strategic Communications Laboratories. It’s not a conspiracy, just that the ruling class are all related.

But back to our history: by the time of the 2003 Iraq War, communications technology had moved on again. As the BBC’s Caroline Wyatt explains in the same blog, “satellite communications are now much more sophisticated, meaning we almost always have our own means of communicating with London. That offers a crucial measure of independence, even if reports still have to be cleared for ‘op sec’ [operational security]. The almost total control by the military of the means of reporting in the Falklands would be unthinkable in most warzones today.”

In February 2004, another major disruption in communications technology began: Facebook was founded. And with it came a whole new propaganda nightmare.

As the same time as this history was unfolding, though, something else vital was happening: neoliberalism.

Looked at one way, neoliberalism is the successor to geographical imperialism as the “most extreme form of capitalism”. It used to be that someone with a small fortune to invest could secure the biggest return by paying someone else to sail overseas, subjugate or kill people (usually people of colour) and steal them and/or their stuff. But they couldn’t keep expanding forever – the world is only so big. And so eventually, wealthy Western investors started to shift much of their focus from opening new markets in ‘far off lands’ to marketising new parts of life at home. Neoliberalism is also therefore this process of marketisation: of shifting decisions from one person one vote, to one pound (or dollar or Yen or Euro) one vote. Or, as Will Davies puts it: “the disenchantment of politics by economics”.

The first Iraq War – the one that “did not take place” – coincided with a key stage in this process: the rapid marketisation (read ‘asset stripping’) of the collapsing Soviet Union, and so the successful encirclement of the globe by Western capital. The second Iraq War was notable for the acceleration of another key stage: the encroachment of market forces into the deepest corner of the state. During the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, according to War on Want, private military companies “burst onto the scene”.

The privatisation of war

An Afghan National Police officer meets a British security contractor during a engagement between U.S. Marines of 1st Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment and Nawa District officials in the Nawa District Bazaar, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, July 22, 2009. (Photo: U.S. Marine Corps/William Greeson)

In a 2016 report, the campaign group War on Want describes how the UK became the world centre for this mercenary industry. You might know G4S as the company which checks your gas meter, but they are primarily the world’s largest mercenary firm, involved in providing ‘security’ in war zones across the planet (don’t miss my colleagues Clare Sambrook and Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi’s excellent investigations of their work in the UK).

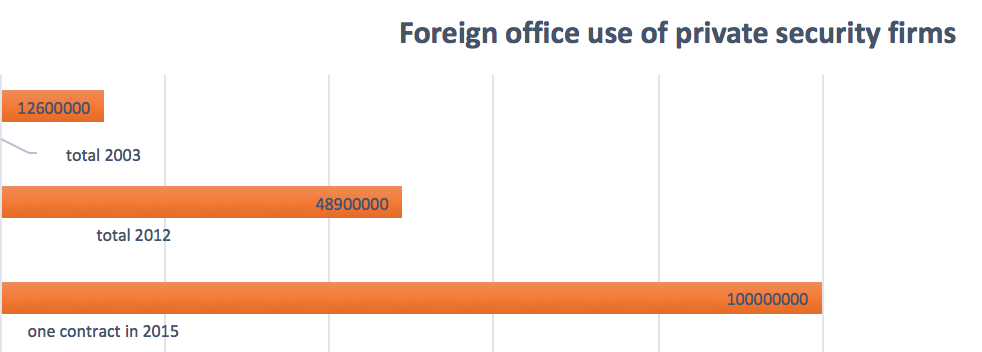

In Hereford alone, near the SAS headquarters, there are 14 mercenary firms, according to War on Want’s report. At the height of the Iraq war, around 80 private companies were involved in the occupation. In 2003, when UK and US forces unleashed “shock and awe” both on the Iraqi people and on their own populations down cable TV wires, the Foreign Office spent £12.6m on British private security firms, according to official figures highlighted by the Guardian. By 2012, that figure had risen to £48.9m. In 2015, G4S alone secured a £100m contract to provide security for the British embassy in Afghanistan.

And just as the fighting was privatised, so too was the propaganda. In 2016, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism revealed that the Pentagon had paid around half a billion dollars to the British PR firm Bell Pottinger to deliver propaganda during the Iraq war. Bell Pottinger, famous for shaping Thatcher’s image, included among its clients Asma Al Assad, wife of the Syrian president. Part of their work was making fake Al Qaeda propaganda films. (The firm was forced to close last year because they made the mistake of deploying their tactics against white people).

Journalist Liam O’Hare has revealed that Mark Turnbull, the SCL and Cambridge Analytica director who was filmed alongside Alexander Nix in the Channel4 sting, was employed by Bell Pottinger in Iraq in this period.

The psychological operations wing of our privatised military: a mercenary propaganda agency.

Like Bell Pottinger, SCL saw the opportunity of the increasing privatisation of war. In his 2006 book “Britain’s Power Elites: The Rebirth of the Ruling Class”, Hywel Williams wrote “It therefore seems only natural that a political communications consultancy, Strategic Communications Laboratories, should have now launched itself as the first private company to provide ‘psyops’ to the military.”

While much of what SCL has done for the military is secret, we do know (thanks, again, to O’Hare) that it’s had contracts from the UK and US departments of defence amounting to (at the very least) hundreds of thousands of dollars. And a document from the National Defence Academy of Latvia that I managed to dig out, entitled “NATO strategic communication: more to be done?” tells us that they were operating in Afghanistan in 2010, and gives some clues about what they were up to:

“more detailed qualitative data gathering operation was being conducted in Maiwand Province by a British company, Strategic Communication Laboratories (SCL) is almost unique in the international contractor community in that it has a dedicated, and funded, behavioural research arm located in the prestigious home of British Science and research, The Royal Institute, London.”

In simple terms, the SCL Group – Cambridge Analytica’s parent firm – is the psychological operations wing of our privatised military: a mercenary propaganda agency.

The skills they developed in the context of warzones shouldn’t be overplayed, but nor should they be underplayed. As far as we can tell, just as the Pentagon used simple tools like choosing where to embed journalists during the Gulf War to spin its version of events, so they mastered the tools of modern communication: Facebook, online videos, data gathering and microtargeting. Such tools aren’t magic (and Anthony Barnett writes well about the risks of implying that they are). They don’t on their own explain either Brexit or Trump (I wrote a plea last year that Remainers in the UK don’t use our investigations as an excuse for failing to engage with the real reasons for the Leave vote). I wouldn’t even use the word “rigging” to describe the impact of these propaganda firms. But they are important.

As the Channel 4 undercover investigation revealed, this work has often been carried out alongside more traditional smear tactics, and – as Chris Wylie explained – in partnership with another nexus in this world: Israel’s conurbation of private intelligence firms, a part of a burgeoning military industrial complex in the country which Israeli activist and writer Jeff Halper argues is a key part of the country’s “parallel diplomacy” drive.

(Of course, this isn’t unique to the UK and Israel. Until Cambridge Analytica achieved global infamy last week, the most prominent mercenary propaganda firm in the world was Peter Theil’s company Palantir (named after the all-seeing eye in Lord of the Rings). Theil, founder of PayPal (with Elon Musk) and an executive of Facebook, wrote a notorious essay in 2009 arguing that female enfranchisement had made democracy untenable and that someone should therefore invent the technology to destroy it. Palantir’s most prominent clients are the United States Intelligence Community, and the US Department of Defence. Cambridge Analytica whistleblower Chris Wylie claimed this week that his firm had worked with Palantir. It’s also noteworthy that one of Palantir’s shareholders is Field Marshal Lord Guthrie, former head of the British Army, and adviser to Veterans for Britain, one of the groups which funnelled money to AggregateIQ ahead of the European referendum. Guthrie also works for Acanum, one of the leading private intelligence agencies, who, in common with Cambridge Analytica’s partners Black Cube, listed Meyer Dagam, the former head of Mossad, as one of their advisers, until he died in 2016. Again, it’s not a conspiracy, it’s just that these guys all know each other. But I digress.)

Back to SCL: why are NATO’s mercenary propagandists getting involved in the US presidential election and – if the growing body of evidence about the link between Cambridge Analytica and AggregateIQ is to be believed – Brexit?

The obvious answer is surely partly true. They could make money doing so, and so they did. If you privatise war, don’t be surprised if military firms start using the tools of war on ‘their own’ side. When Eisenhower warned of the Military Industrial Complex, he was thinking about physical weapons. But, just as unregulated semi-automatics invented for soldiers end up going off in American schools, it shouldn’t be any kind of surprise that the weapons of information war are going off in Anglo-American votes.

But in a more general sense, this whole history is exactly what Brexit was about for many of the powerful people who pushed for it. As we’ve been investigating the secret donation which paid for the DUP Brexit campaign, we keep coming across this web of connections. Priti Patel worked for Bell Pottinger in Bahrain. Richard Cook, the front man for the secret donation to the DUP, set up a business in 2013 with the former head of Saudi intelligence and a Danish man involved in running guns to Hindu radicals who told us he was a spy. David Banks, who ran Veterans for Britain, worked in PR in the Middle East for four years – and Veterans for Britain more generally is full of these contacts.

I could go on. My suspicion is that this isn’t because there’s some kind of conspiracy revolving around a group of ex-spooks. It’s about the fact that power comes from networks of people, and the wing of the British ruling class which was in and around the military is moving rapidly into the world of privatised war. And those people have a strong ideological and material interest in radical right politics.

“The most corrupt country on Earth”

Iraqis pass by a British tank as they flee Basra, southern Iraq, as smoke looming over the city can be seen in the distance, March 29, 2003. (AP/Anja Niedringhaus)

Another way to see it is like this: Britain has lost most of its geographical empire. And most of our modern politics is about the ways in which different groups struggle to come to terms with that fact. For a large portion of the ruling establishment, this involves attempting to reprise the glory days by placing the country at the centre of two of the nexuses which define the modern era.

The UK and its Overseas Territories have already become by far the most significant network of tax havens and secrecy areas in the world, making us the global centre for money laundering and therefore, as Roberto Saviano, the leading expert on the mafia argues, the most corrupt country on earth. And just as countries with major oil industries have major oil lobbies, the UK has a major money laundry-lobby.

Pesky EU regulations have long frustrated the dreams of these people, who wish our island nation to move even further offshore and become even more of a tax haven. And so for some Brexiteers – this money laundry lobby – there was always strong incentive to back a Leave vote: European Research Group statements going back 25 years show as much.

But what the Cambridge Analytica affair reminds us of is that this is not just about the money laundry lobby (nor the agrochemical lobby). Another group with a strong interest in pushing such deregulation, dimming transparency, hyping Islamophobia in America and turning peoples against each other is our flourishing mercenary complex – one of the only other industries in which Britain leads the world. And so it’s no surprise that its propaganda wing has turned the skills it’s learned in towards its desired political outcomes.

In his essay, Baudrillard argued that his observations about the changes in military propaganda told us something about the then new post-Cold War era. Only two years after Tim Berners Lee invented the World Wide Web, he wrote a sentence which, for me, teaches us more about the Cambridge Analytica story than much of the punditry that we’ve seen since: “just as wealth is no longer measured by the ostentation of wealth but by the secret circulation of capital, so war is not measured by being unleashed but by its speculative unfolding in an abstract, electronic and informational space.”

Cambridge Analytica is what happens when you privatise your military propaganda operation. It walked into the space created when social media killed journalism. It is yet another example of tools developed to subjugate people elsewhere in the world being used on the domestic populations of the Western countries in which they were built. It marks the point at which neoliberal capitalism reaches its zenith, and ascends to surveillance capitalism. And the best possible response is to create a democratic media which can’t be bought by propagandists.

Top Photo | American tanks arrive in Baghdad in 2003, by Technical Sergeant John L. Houghton, Jr., United States Air Force. (Public Domain)

Adam Ramsay is the Co-Editor of openDemocracyUK and also works with Bright Green. Before, he was a full time campaigner with People & Planet. You can follow him at @adamramsay.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario