TARCOTECA counterinfo

Join the Resistance, contact your local groups! tarcoteca@riseup.net

La Tarcoteca

viernes, 7 de octubre de 2022

🔴 FREE ASSANGE HUMAN CHAIN - SAT 8th OCT 🔴 #FreeAssangeNow

domingo, 11 de septiembre de 2022

The Legacy of the St. Imier Congress

This September 15th marks the 150th anniversary of the St. Imier Congress in Switzerland, when delegates representing sections of the International Workingmen’s Association reconstituted the International along anti-authoritarian lines, following the expulsion of Michael Bakunin and James Guillaume from the International at the behest of Marx and Engels at the Hague Congress on September 7, 1872. I prepared the following article on the St. Imier Congress and its aftermath for Black Flag Anarchist Review’s Summer 2022 issue on anarchism and the First International. The special conference to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the St. Imier Congress has been postponed to July 2023:www.Anarchy2023.org.Saint Imier

The September 1872 St. Imier Congress of federalist and anti-authoritarian sections and federations of the International Workingmen’s Association (the “IWMA”), otherwise known as the “First International,” marks a watershed moment in the history of socialism and anarchism.

Just over a week earlier, at the Hague Congress of the International (September 2 – 7, 1872), Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels had engineered the expulsion of Michael Bakunin and James Guillaume from the International on trumped up grounds, and then had the General Council of the International transferred from London to New York, despite the General Council having been granted increased powers to ensure ideological uniformity. The Hague Congress had also passed a resolution mandating the formation of national political parties for the purpose of achieving political power.

While Marx and Engels’ allies at the Hague Congress, notably the French Blanquists (followers of Auguste Blanqui, a radical French socialist who advocated revolutionary dictatorship), had supported the expulsions of Bakunin and Guillaume, they were taken by surprise when Marx and Engels succeeded in transferring the executive power of the International, the General Council, to New York, and had quit the International in disgust. The New York based “International” quickly became an irrelevant rump.

A majority of the International’s sections and federations did not support the resolutions of the Hague Congress. Barely a week after the Hague Congress, several of them held their own congress in St. Imier, Switzerland, where they reconstituted the International independent of the shell organization now controlled by Marx and Engels through the General Council.

The opponents of the Marxist controlled International were united in their opposition to the concentration of power in the General Council, regardless of whether the Council sat in London or New York. They also shared a commitment to directly democratic federalist forms of organization. Some were completely opposed to the formation of working class political parties to achieve state power, while others were opposed to making that a mandatory policy regardless of the views of the membership and local circumstances. The reconstituted anti-authoritarian wing of the International was to have anarchist, syndicalist and, for a time, reformist elements.

The St. Imier Congress began on September 15, 1872, just eight days after the Hague Congress. It was attended by delegates from Spain, France, Italy and Switzerland, including Guillaume and Adhémar Schwitzguébel from Switzerland; Carlo Cafiero, Errico Malatesta, Giuseppi Fanelli, and Andrea Costa from Italy; Rafael Farga-Pellicer and Tomás González Morago from Spain; and the French refugees, Charles Alerini, Gustave Lefrançais, and Jean-Louis Pindy. Bakunin, although living in Switzerland, attended as an Italian delegate.

A “regional” congress of the Swiss Jura Federation was held in conjunction with the “international” congress, with many of the same delegates, plus members of the Slav Section, such as Zamfir Arbore (who went under the name of Zemphiry Ralli) and other French speaking delegates, including Charles Beslay, an old friend of Proudhon’s who went into exile in Switzerland after the brutal suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871.

Virtually all of the participants were either anarchists or revolutionary socialist federalists, and many of them went on to play important roles in the development of anarchist and revolutionary socialist movements in Europe.

The assembled delegates adopted a federalist structure for a reconstituted International (or the “anti-authoritarian International”), with full autonomy for the sections, declaring that “nobody has the right to deprive autonomous federations and sections of their incontrovertible right to decide for themselves and to follow whatever line of political conduct they deem best.” For them, “the aspirations of the proletariat can have no purpose other than the establishment of an absolutely free economic organization and federation, founded upon the labour and equality of all and absolutely independent of all political government.” Consequently, turning the Hague Congress resolution regarding the formation of political parties for the purpose of achieving political power on its head, they proclaimed that “the destruction of all political power is the first duty of the proletariat.”

With respect to organized resistance to capitalism, the delegates to the St. Imier Congress affirmed their position that the organization of labour, through trade unions and other working class forms of organization, “integrates the proletariat into a community of interests, trains it in collective living and prepares it for the supreme struggle,” through which “the privilege and authority” maintained and represented by the State will be replaced by “the free and spontaneous organization of labour.”

While the anti-authoritarian Internationalists entertained no illusions regarding the efficacy of strikes in ameliorating the condition of the workers, they regarded “the strike as a precious weapon in the struggle.” They embraced strikes “as a product of the antagonism between labour and capital, the necessary consequence of which is to make workers more and more alive to the gulf that exists between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat,” bolstering their organizations and preparing them “for the great and final revolutionary contest which, destroying all privilege and all class difference, will bestow upon the worker a right to the enjoyment of the gross product of his labours.”

Here we have the subsequent program of anarcho-syndicalism: the organization of workers into trade unions and similar bodies, based on class struggle, through which the workers will become conscious of their class power, ultimately resulting in the destruction of capitalism and the state, to be replaced by the free federation of the workers based on the organizations they created themselves during their struggle for liberation.

The resolutions from the St. Imier Congress received statements of support from the Italian, Spanish, Jura, Belgian and some of the English speaking American federations of the International, with most of the French sections also approving them. In Holland, three out of the four Dutch branches sided with the Jura Federation and the St. Imier Congress. The English Federation, resentful of Marx’s attempts to keep it under his control, rejected “the decisions of the Hague Congress and the so-called General Council of New York.” While the longtime English member of the International, John Hales, did not support revolution, he advised the Jura Federation that he agreed with them on “the principle of Federalism.” At a congress of the Belgian Federation in December 1872, the delegates there also repudiated the Hague Congress and the General Council, supporting instead the “defenders of pure revolutionary ideas, Anarchists, enemies of all authoritarian centralisation and indomitable partisans of autonomy.”

However, there was a tension in the resolutions adopted at the St. Imier Congress. On the one hand, one resolution asserted the “incontrovertible right” of the International’s autonomous federations and sections “to decide for themselves and to follow whatever line of political conduct they deem best.” On the other hand, another resolution asserted that “the destruction of all political power is the first duty of the proletariat.”

The resolution regarding the autonomy of the federations and sections in all matters, including political action, was meant to maintain the International as a pluralist federation where each member group was free to follow their own political approach, so that both advocates of participation in electoral activity and proponents of revolutionary change could co-exist.

However, the call for the destruction of all political power expressed an anarchist position. The two resolutions could only be reconciled if the destruction of political power was not necessarily the “first duty of the proletariat,” but could also be regarded as a more distant goal to be achieved gradually, along with “the free and spontaneous organization of labour.”

The tension between these two resolutions continued to exist within the reconstituted International for several years. James Guillaume supported political pluralism within the International and sought to convince some of the sections and federations that had gone along with Marx, such as the Social Democrats in Germany, to rejoin the anti-authoritarian International, and to keep the English Internationalists who had rejected Marx’s centralist approach, such as Hales, within the reconstituted International.

Although the German Social Democrats never officially joined the reconstituted International, two German delegates attended the 1874 Brussels Congress. English delegates attended both the September 1873 Geneva Congress and the September 1874 Brussels Congress, where there was an important debate regarding political strategy, including whether there was any positive role for the state.

The Geneva Congress in September 1873 was the first full congress of the reconstituted International. It was attended by delegates from England, France, Spain, Italy, Holland, Belgium and Switzerland. The English delegates, John Hales and Johann Georg Eccarius (Marx’s former lieutenant), had been members of the original International. They were interested in reviving the International as an association of workers’ organizations, and in disavowing the Marxist controlled General Council and International that had been transferred by Marx and Engels to New York. They had not become anarchists, as Hales made clear by declaring anarchism “tantamount to individualism… the foundation of the extant form of society, the form we desire to overthrow.” Accordingly, from his perspective, anarchism was “incompatible with collectivism” (a term which at the time was synonymous with socialism).

The Spanish delegate, José Garcia Viñas, responded that anarchy did not mean disorder, as the bourgeois claimed, but the negation of political authority and the organization of a new economic order. Paul Brousse, a French refugee who had recently joined the Jura Federation in Switzerland, agreed, arguing that anarchy meant the abolition of the governmental regime and its replacement by a collectivist economic organization based on contracts between the communes, the workers and the collective organizations of the workers, a position that can be traced back to Proudhon.

Most of the delegates to the Congress were anti-authoritarian federalists, and the majority of them were clearly anarchist in orientation, including “Farga-Pellicer from Spain, Pindy and Brousse from France, Costa from Italy, and Guillaume and Schwitzguebel from Switzerland.” Also within the anarchist camp were Garcia Viñas from Spain, who was close to Brousse, Charles Alerini, a French refugee now based in Barcelona associated with Bakunin, Nicholas Zhukovsky, the Russian expatriate who remained close to Bakunin, François Dumartheray (1842-1931), another French refugee who had joined the Jura Federation, Jules Montels (1843-1916), a former provincial delegate of the Commune who was responsible for distributing propaganda in France on behalf of the exiled group, the Section of Revolutionary Socialist Propaganda and Action, and two of the Belgian delegates, Laurent Verrycken and Victor Dave.

The American Federal Council sent a report to the Congress, in which it indicated its support for the anti-authoritarian International. The Americans were in favour of freedom of initiative for the members, sections, branches and federations of the International, and agreed with limiting any general council to purely administrative functions. They felt that it should be up to each group to determine their own tactics and strategies for revolutionary transformation. They concluded their address with “Long live the social revolution! Long live the International.”

At the 1873 Geneva Congress, it was ultimately agreed to adopt a form of organization based on that followed by the Jura Federation, with a federal bureau to be established that “would be concerned only with collecting statistics and maintaining international correspondence.” As a further safeguard against the federal bureau coming to exercise authority over the various sections and branches, it was to “be shifted each year to the country where the next International Congress would be held.”

The delegates continued the practice of voting in accordance with the mandates that had been given to them by their respective federations. Because the International was now a federation of autonomous groups, each national federation was given one vote and the statutes were amended to explicitly provide that questions of principle could not be decided by a vote. It was up to each federation to determine its own policies and to implement those decisions of the congress that it accepted.

Eccarius also attended the next Congress in Brussels in September 1874 as the English delegate. He and the two German delegates remained in favour of a workers’ state and participation in conventional politics, such as parliamentary elections.

The most significant debate at the Brussels Congress was the one over public services. César De Paepe, on behalf of the Belgians, argued that if public services were turned over to the workers’ associations, or “companies,” the people would simply “have the grim pleasure of substituting a worker aristocracy for a bourgeois aristocracy” since the worker companies, “enjoying a natural or artificial monopoly… would dominate the whole economy.” Neither could all public services be undertaken by local communes, since “the most important of them,” such as railways, highways, river and water management, and communications, “are by their very nature fated to operate over a territory larger than that of the Commune.” Such intercommunal public services would therefore have to be run by delegates appointed by the federated communes. De Paepe claimed that the “regional or national Federation of communes” would constitute a “non-authoritarian State… charged with educating the young and centralizing the great joint undertakings.”

However, De Paepe took his argument one step further, suggesting that “the reconstitution of society upon the foundation of the industrial group, the organization of the state from below upwards, instead of being the starting point and the signal of the revolution, might not prove to be its more or less remote result… We are led to enquire whether, before the groupings of the workers by industry is sufficiently advanced, circumstances may not compel the proletariat of the large towns to establish a collective dictatorship over the rest of the population, and this for a sufficiently long period to sweep away whatever obstacles there may be to the emancipation of the working class. Should this happen, it seems obvious that one of the first things which such a collective dictatorship would have to do would be to lay hands on all the public services.”

De Paepe’s position was opposed by several delegates, including at least one of the Belgians, Laurent Verrycken. He spoke against any workers’ state, arguing that public services should be organized by “the free Commune and the free Federation of communes,” with the execution of the services being undertaken by the workers who provided them under the supervision of the general association of workers within the Commune, and by the Communes in a regional federation of Communes. Farga Pellicer (“Gomez”), on behalf of the Spanish Federation, said that “for a long time they had generally pronounced themselves in favour of anarchy, such that they would be opposed to any reorganization of public services that would lead to the reconstitution of the state.” For him, a “federation of communes” should not be referred to as a “state,” because the latter word represented “the political idea, authoritarian and governmental,” as De Paepe’s comments regarding the need for a “collective dictatorship” revealed.

The most vocal opponent of De Paepe’s proposal was Schwitzguébel from the Jura Federation. He argued that the social revolution would be accomplished by the workers themselves “assuming direct control of the instruments of labor;” thus, “right from the first acts of the Revolution, the practical assertion of the principle of autonomy and federation… becomes the basis of all social combination,” with “all State institutions,” the means by “which the bourgeoisie sustains its privileges,” foundering in the “revolutionary storm.” With “the various trades bodies” being “masters of the situation,” having “banded together freely for revolutionary action, the workers will stick to such free association when it comes to organization of production, exchange, commerce, training and education, health, and security.”

On the issue of political action, the Belgian delegates to the Brussels Congress continued to advocate working outside of the existing political system, albeit partly because they did not yet have universal suffrage in Belgium. Nevertheless, they claimed they did not expect anything from the suffrage or from parliament, and that they would continue to organize the workers into the trades bodies and federations through which the working class would bring about the social revolution, revealing that, as a group, the Belgian Federation did not yet share De Paepe’s doubts that the free federation of the producers would not be the means, but only the result, of a revolution.

The French delegate indicated that the French Internationalists remained anti-political, seeking to unite the workers “through incessant propaganda,” not to conquer power, but “to achieve the negation of all political government,” organizing themselves for “the true social revolution.”

The Congress ultimately declared that it was up to each federation and each democratic socialist party to determine for themselves what kind of political approach they should follow. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that as of September 1874, the majority of the anti-authoritarian International continued to embrace an anarchist or revolutionary syndicalist position. At the end of the 1874 Brussels Congress, the delegates issued a manifesto confirming their commitment to collectivism, workers’ autonomy, federalism and social revolution; in a word, nothing less than the original goal of the International itself: “the emancipation of the workers by the workers themselves.”

By the time of the October 1876 Bern Congress, the English had ceased participating in the anti-authoritarian International. The debate over the “public service” state continued, with De Paepe now openly advocating that the workers “seize and use the powers of the State” in order to create a socialist society. Most of the delegates rejected De Paepe’s position, including Guillaume and Malatesta.

Malatesta argued for “the complete abolition of the state in all its possible manifestations.” While Guillaume and some of the other veteran anti-authoritarians liked to avoid the “anarchist” label, Malatesta declared that “Anarchy, the struggle against all authority … always remains the banner around which the whole of revolutionary Italy rallies.” Both Malatesta and Guillaume made clear that in rejecting the state, even in a “transitional” role, they were not advocating the abolition of public services, as De Paepe implied, but their reorganization by the workers themselves.

In September 1877, the anti-authoritarian International held a congress in Verviers, Belgium, which was to be its last. Guillaume and Peter Kropotkin, now a member of the Jura Federation, attended from Switzerland. The French refugees, Paul Brousse and Jules Montels, also attended. In addition, there were Garcia Viñas and Morago from Spain. Otto Rinke and Emil Werner, both anarchists, “represented sections in both Switzerland and Germany, while there was a strong delegation from the Verviers region, the last stronghold of anarchism in Belgium.” Costa represented Greek and Egyptian socialists who were unable to attend, as well as the Italian Federation.

De Paepe did not attend the Congress, as he was preparing for his rapprochement with social democracy and parliamentary politics at the World Socialist Congress that was about to begin in Ghent. In anticipation of the Ghent Congress, the delegates to the Verviers Congress passed several resolutions emphasizing the limited bases for cooperation between the now predominantly anarchist oriented anti-authoritarian International and the social democrats. For the Verviers delegates, collective property, which they defined as “the taking of possession of social capital by the workers’ groups” rather than by the State, was an immediate necessity, not a “far-off ideal.”

On the issue of political action, the delegates indicated that class antagonism could not be resolved by government or some other political power, but only “by the unified efforts of all the exploited against their exploiters.” They vowed to combat all political parties, regardless of “whether or not they call themselves socialists,” because they did not see electoral activity as leading to the abolition of capitalism and the state. While the majority of the delegates therefore supported anti-parliamentary socialism, none of the policies endorsed at the congresses of the reconstituted International were binding on the International’s member groups, who remained free to adopt or reject them.

With respect to trade union organization, the delegates confirmed their view that unions that limit their demands to improving working conditions, reducing the working day and increasing wages, “will never bring about the emancipation of the proletariat.” Trade unions, to be revolutionary, must adopt, “as their principal goal, the abolition of the wage system” and “the taking of possession of the instruments of labour by expropriating them” from the capitalists.

Unsurprisingly, despite Guillaume’s hopes for reconciliation between the social democratic and revolutionary anarchist wings of the socialist movement, no such reconciliation was reached at the Ghent Congress, or at any subsequent international socialist congresses, with the so-called “Second International” finally barring anarchist membership altogether at its 1896 international congress in London.

Despite the formal position taken at the St. Imier Congress regarding the freedom of each member group of the reconstituted International to determine its own political path, reaffirmed at the 1873 Geneva Congress, because the majority of the delegates to the anti-authoritarian International’s congresses, and its most active members, were either anarchists or revolutionary socialists opposed to participation in electoral politics, it was not surprising that eventually those in favour of parliamentary activity would find other forums in which to participate, rather than continuing to debate the issue with people who were not committed to an electoral strategy.

Only a minority of member groups in the reconstituted International ever supported or came to support a strategy oriented toward achieving political power – the English delegates, a few of the German delegates who did not officially represent any group, and then a group of Belgians, with the Belgian Federation being split on the issue. Other than the debate on the “public service state,” which again only a minority of delegates supported, most of the discussions at the reconstituted International’s congresses focused on tactics and strategies for abolishing the state and capitalism through various forms of direct action, in order to achieve “the free and spontaneous organization of labour” that the St. Imier Congress had reaffirmed as the International’s ultimate goal.

For example, there were ongoing debates within the reconstituted International regarding the role and efficacy of strikes and the use of the general strike as a means for overthrowing the existing order. Any kind of strike activity had the potential to harm the electoral prospects of socialist political parties, an issue that had arisen in the Swiss Romande Federation prior to the split in the original International. Once the focus becomes trying to elect as many socialist or workers’ candidates as possible to political office in order to eventually form a government, the trade unions and other workers’ organizations are then pressured to tailor their tactics to enhance the prospects of the political parties’ electoral success. Both the immediate and long term interests of the workers become subordinate to the interests of the political parties.

After socialist parties were established in western Europe in the 1880s, and workers began to see how their interests were being given short shrift, there was a resurgence in autonomous revolutionary trade union activity, leading to the creation of revolutionary syndicalist movements in the 1890s. Some of the syndicalist organizations, such as the French Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT), adopted an “apolitical” stance, similar to the official stance of the reconstituted International. The CGT was independent of the political parties but members were free to support political parties and to participate in electoral activities, just not in the name of the CGT. Independence from the political parties was an essential tenet of the original CGT, so that it could pursue its strategy of revolutionary trade union organization and direct action unimpeded by the demands and interests of the political parties.

The majority of those who chose to remain active in the reconstituted International based on the resolutions adopted at the St. Imier Congress believed above all that the International should not only remain independent of the socialist political parties, but that the International should continue to pursue its goal of achieving “the free and spontaneous organization of labour” through the workers’ own autonomous organizations, free of political interference and control. For those who chose instead to throw their lot in with the political parties, there really wasn’t much reason for them to remain involved in such an organization, even though there was no formal bar to their continued membership and participation. It was simply time for them to part ways.

sábado, 9 de julio de 2022

Alex Krainer: The Shocking Truth of the 1938 Munich Agreement. Anglo-German Nazi Connection

martes, 19 de abril de 2022

Libertarian Geopolitics: it is not Ukraine, the US or Russia, it is the War for the New World to Be Born

We thought that this was a dead debate, but due to the avalanche of anti-Russian, pro-Ukrainian, pro-American and pro-NATO anarchist publications, has made us take a brief look at the different situations and conditions to decide which option is more in line with the libertarian ideal and if we anarchist can reach any kind of consensus about.

Supporting the Dombass

Our position coincides, to our regret, with that of Russia

Ukraine

Russia

USA

Geopolitical assessment of political support

Supporting Ukraine

Supporting USA

Supporting Russia

Russia is for now the lesser evil.

Can Russia be supported?

Rojava 2012

Venezuela 2014

Catalonia 2017

Belarus 2020

The 'Dombass Solution'

Dilemmas will keep rising up

The new world to be born

Contradictions and Coincidences

Collaborate with fascism? Never! Double Front

Conclusions

To know more

Gira europea trascendental de Biden para impulsar la 3GM 22.3.2022Análisis militar Ucrania vs Rusia: de la Guerra moderna a la Clásica en la Era del Descenso 21.3.2022

Más sobre las respuestas libertarias a la guerra | Alasbarricadas.org 15.3.2022

La visión de Ucrania, la visión de Rusia | Alasbarricadas.org 6.3.2022

Europa Battle Zone: Rusia cede a las provocaciones de Estados Unidos, y ésta se cobra tres piezas. Geopolítica 28.2.2022

La Anarquía y sus Aliados: el 'Frente Unido' y 'Agrupación de Tendencia' 10.1.2022 Tommy Lawson. Libro en PDF

domingo, 20 de marzo de 2022

USA, Listen, You’re About To Sink — Gonzalo Lira. Video

sábado, 5 de marzo de 2022

The only war to end all wars…

The Russian onslaught on Ukraine reminds the West that war can happen. We look on in horror as people “looking like us” in towns “like ours” go to shelters or wade through rubble. It seemed unimaginable to generations who believed war all but abolished.

This is not the reality for most of the planet though. Our relative peace for nearly 80 years has been bought at the expense of vast swathes of the world where superpower conflicts have been fought by bloody proxies. We have seen this most recently in Ethiopia and Tigre, in Sudan and Central Africa, Somalia, the Sahel and Middle East, Myanmar and Sri Lanka going all the way back to 1945.In almost every country and every inhabited continent millions have perished miserably to maintain the Western fiction of a New World Order’s international peace. As revolutionaries and internationalists, the war comes as a tragic confirmation that our system of exploitation and profit and endless bloody conflict are inseparable. They are not only inseparable but a causal and defining cog in the wheel of planetary destruction grinding the pandemic and climate change.

There is no victimless exploitation, bloodless war, virtuous state, or egalitarian capitalism. They are more like the apocryphal horseman of a stoppable apocalypse. Against this background, equally largely hidden from view in the western mind has been the struggle of millions in continuous resistance to both war, exploitation and annihilation. The struggle that thrives on every inhabited continent and of which we count ourselves.

On our own it feels insurmountable but collectively we grow in strength confidence and skills. No action is too small to start though its relevance is crucial. From food banks to social centres, strike committees to picket lines. Marches to demonstrations, blockades to occupations. Coming together in free association to share, develop and challenge. To build anew as we grow and break their rules and constraints. From refusal to re-imagining and from resistance to revolution.

The war in Ukraine is not the only one but one of many, and those wars are essential to the nature of capitalism, power and the state. More wars are coming and so is more resistance. Those who order them, don’t fight, those forced to fight come from the same class and communities as us. By building resistance in our communities we can build the power to refuse their war and replace it with our own, class war. The only war that will end all wars.

*Add- This article was sent to us from an ex-member of Manchester Anarchist Federation

sábado, 20 de noviembre de 2021

The New Republic, “Were the Earliest Societies Anarchists?”

His final book, The Dawn of Everything, a co-written study of the earliest forms of social organization, caps a large and variegated output. Debt, controversial but enormously erudite and startlingly original, was his best-known work, though his two explicitly political volumes were also bestsellers: The Democracy Project (2013), a chronicle of Occupy Wall Street, followed by a scathing critique of American society and politics; and Bullshit Jobs (2018), an acerbic history and analysis of pointless drudgery (an important theme in The Dawn of Everything as well). The Utopia of Rules (2015) gathered several celebrated essays, including “The Utopia of Rules, or Why We Really Love Bureaucracy After All” and “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit.” He was on quite a roll in his last decade. But the above was not all he was doing.

In a moving foreword to The Dawn of Everything, Graeber’s co-author, David Wengrow, an archaeology professor at University College London, described their 10-year collaboration on “a new history of humankind”: a period when “it was not uncommon for us to talk two or three times a day. We would often lose track of who came up with what idea or which new set of facts and examples.… We got to the end just as we’d started, in dialogue, with drafts passing constantly back and forth between us as we read, shared and discussed the same sources, often into the small hours of the night.” It sounds idyllic—a form of collaboration much like those that he and Wengrow argue underpinned some of the earliest human societies.

There is a Standard Version of deep history, those long ages before writing (roughly 40,000–12,000 B.C.E.), when humans left behind traces—suggestive but not definitive—of culture and technology. The Standard Version is a species of technological determinism, in which forms of society correspond to modes of production. There have been four main social forms, according to this theory: bands, mobile groups of a few families; tribes, of perhaps 100 members, moving a few times a year; chiefdoms, hundreds strong, centered in one place but with smaller groups occasionally moving away for various reasons; and states, with thousands of members, centered in cities, and with a central government more or (usually) less accountable to the populace. To each of these forms corresponded a mode of subsistence: respectively, hunting/gathering; gardening/foraging/herding; farming; and industry. Political forms followed a closely parallel evolution: egalitarianism, private property, kingship (often just ceremonial), and the bureaucratic state. Each of these stages was more productive and more civilized than the last, but also less equal and less free.

In addition to its pleasing symmetry, the Standard Version has a certain pathos that appeals to supposedly tough-minded scientists. Civilization is a stern fate, on this view: We can only attain modernity’s deepest satisfactions by giving up the mobility, spontaneity, and nonchalance of our free-spirited but immature ancestors. We moderns—and especially intellectuals, who grasp this painful dilemma most fully—become tragic heroes of a sort.

Graeber and Wengrow, however, are intent on blowing up the Standard Version in The Dawn of Everything. It was an understandable attempt to extrapolate from very limited data (and, in some cases, a less excusable attempt to retroactively justify Western colonialism). But in the last few decades, a mass of new evidence from archaeology and anthropology has appeared, leaving it all but unsalvageable. Again and again, among the Kwakiutl, Nambikwara, Inuit, Lakota, and innumerable others, from the Amazon to the Arctic Circle to Central Africa to the Great Plains, and in all periods from the Upper Paleolithic to the nineteenth century, archaeologists have discovered variety where the Standard Version predicted uniformity.

Until around 10,000 B.C., according to the eminent primatologist Christopher Boehm, articulating the scholarly consensus, humans lived in “societies of equals, and outside the family there were no dominators.” In such societies, where supposedly no distinctions of power or rank were observed in life, it seems unlikely they would have been observed in death. They were, however, and regularly. Rich burials—in unusually large graves or with ornaments, tools, textiles, or weapons, sometimes in profusion—have been found on every continent, often dating to millennia before social distinctions of any sort were supposed to have arisen in human societies. The egalitarian bands of prehistory, never solidly based on evidence, may soon disappear into myth.

Monumental architecture is more evidence against the standard evolutionary scheme. In southern Turkey, for example, there is an ensemble of 20 stone temples, about as large as Stonehenge (which dates from 3000 B.C.), with carved portraits of animals on the pillars. It dates from 9000 B.C. In Poverty Point, Louisiana, a network of enormous mounds and ridges stretches out across 400 acres or so. Constructed in 1600 B.C. (by moving a million cubic meters of earth), it may have been a trading center or a ritual center. Its builders seem to have been hunters, fishers, and foragers. Across Eastern Europe is a line of “mammoth houses,” enclosures up to 40 feet in diameter made of mammoth hides stretched over poles, constructed between 25,000 and 12,000 years ago, obviously by at least part-time hunters. Every year, more very old monuments constructed by nonfarming, non-state people are discovered, making it harder to believe that such achievements are only possible, as the conventional wisdom has it, on the basis of agricultural surpluses and bureaucratic expertise.

Evidence of occupational variety at many sites calls for explanation: It seems unlikely that, at the same moment in a given area, one group consisted of full-time agriculturalists, another of full-time foragers, and another full-time pastoralists. It now appears that seasonality was very common, with groups changing not only their way of procuring food one or more times a year, but authority relations and other customs as well. Members of a North American Plains tribe, for example, were foragers and herders for most of the year, with very lax discipline both at home and toward tribal leaders. During the great annual buffalo hunt, however, the tribe became quite hierarchical; in particular, there were “buffalo police” who enforced norms of cooperation and distribution very strictly and even had the power to impose capital punishment on the spot for sufficiently grave violations. Most indigenous Amazonian societies had different authority structures at different times of year. Perhaps the best-known example is from the Arctic, where Inuit fathers exercised strict patriarchal authority in summer, while winter, lived more inside, was something of a saturnalia, with spouse-swapping and children running free.

By and large, anthropologists have not made much of seasonality. (Interestingly, most of those who have done so have been anarchist-leaning: Marcel Mauss, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Robert Lowie, Pierre Clastres.) Graeber and Wengrow make a great deal of it.

It is difficult for some—perhaps most—of us to attribute so advanced a political and philosophical consciousness to our remote ancestors. Perhaps, Graeber and Wengrow suggest, that is the problem: Our unshakable conviction that modernity spells progress and liberation prevents us from seeing that, in many times and places, premodern life was actually more rational and free.

Though combative, The Dawn of Everything is an upbeat book. Its debunking energies mainly go to refuting the conventional wisdom at its most discouraging. For example, anthropologists and archaeologists (like most everyone else) tend to assume there is an inverse relation between scale and equality; that the greater the number of people who need to be organized to work or live or fight together, the more coercion will be necessary. Cities represent a scaling up of population, and therefore, naturally, of mechanisms of control. And where did cities come from?

The conventional story looks for the ultimate causes in technological factors: Cities were a delayed, but inevitable, effect of the “Agricultural Revolution,” which started populations on an upward trajectory, and set off a chain of other developments, for instance in transport and administration, which made it possible to support large populations living in one place. These large populations then required states to administer them.

This conventional story is being undermined by new archaeological evidence, especially from the largest prehistoric cities, in Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica. Those “large populations living in one place”—peasantries—do not show up until later in the histories of most large cities. Initially, besides farmers drawn to a fertile floodplain, there were equal numbers of hunters, foragers, and fishers, and sometimes very large ceremonial or ritual centers. What there don’t seem to have been, by and large, were ruling classes. The conventional assumption—amounting almost to a Weltanschauung—that civilization marches in lockstep with state authority seems to be tottering.

The Agricultural Revolution is another key element of the Standard Version: a swift and mostly complete transition from mobile, egalitarian, healthy foragers, relatively few in number, lacking the concept of private property, and living on wild resources, to farming populations, numerous, sedentary, class-stratified, disease-ridden, and producing a surplus of food. The consequence, as noted above, was cities, and the inevitable concomitant of cities was states. But this turns out to be far too neat. As recent evidence shows, many populations took up farming and then went back to foraging. Many foraging communities were far more authoritarian than farming communities. And in quite a few places, the transition from foraging to farming took thousands of years. It may be necessary to rechristen the Agricultural Revolution as the Agricultural Slow Walk.

Prehistory, Graeber and Wengrow insist, is vastly more interesting than scholars knew until recently. And not just more interesting, but more inspiring as well: “It is clear now that human societies before the advent of farming were not confined to small, egalitarian bands. On the contrary, the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of several bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms, far more than it does the drab abstractions of evolutionary theory.” “Carnival” brings to mind Occupy, which, along with this book, testifies to David Graeber’s admirable energy, imagination, and love of freedom.

For all its historical and theoretical brilliance, The Dawn of Everything does not wholly vindicate the anarchist philosophical framework in which the argument is set. Graeber and Wengrow do not exactly preach anarchism, but the moral of their long and immensely rich study is clear: Relations of authority are the most important and revealing things about any society, small or large, and no one should ever be subject to any authority she hasn’t chosen to be subject to.

Who could disagree—as long as it’s understood that accepting citizenship in a democratic polity means choosing to be subject to its authority? This is a window on a long-standing quarrel between anarchists and their less glamorous political cousins, socialists and social democrats. As one of the latter tribe, I confess that The Dawn of Everything did get a rise out of me now and then. For one thing, nearly everyone to the left of Genghis Khan has a sentimental fondness for the European Enlightenment—it’s where the critical spirit found its voice. Graeber and Wengrow think it’s vastly overrated. Enlightenment thinkers weren’t particularly original, they write; their political ideas came mostly from China and from Native Americans. The proof is that Leibniz and Montesquieu praised the Chinese civil service and recommended it to European rulers while Native Americans who visited Europe impressed the philosophers so much that many of them put the visitors into their philosophical dialogues.

Native American political thought is certainly impressive, and Graeber and Wengrow expound it superlatively well. Still, no one has claimed (as far as I know) that Europe got from Native Americans the ideas of habeas corpus, an independent judiciary, trial by jury, a free press, religious disestablishment, or a written constitution with enumerated rights; or that Adam Smith got from them the idea of labor unions, free education for workers, or income redistribution, all of which he argued for in The Wealth of Nations (though few conservatives have noticed). Perhaps the American left should take a break from trying to subvert the Enlightenment until the American right stops trying to roll it back.

Graeber and Wengrow’s second foray into socialist-/social democrat–baiting is more surprising. Equality, the cherished ideal of most leftists past and present, seems to them a theoretical and strategic dead end, a mere “technocratic” reform. They dismiss, even mock, equality as a goal:

To create a society of true equality today, you’re going to have to figure out a way to go back to becoming tiny bands of foragers again with no significant personal property. Since foragers require a pretty extensive territory to forage in, this would mean having to reduce the world’s population by something like 99.9 percent. Otherwise, the best we can hope for is to adjust the size of the boot that will forever be stomping on our faces; or, perhaps, to wrangle a bit more wiggle room in which some of us can temporarily duck out of its way.

Equality is not only an unworthy goal; it is not even an intelligible one: “it remains entirely unclear what ‘egalitarian’ even means.” Does it? It seems clear enough to me: a society with a Gini coefficient below 0.2 (Graeber and Wengrow persistently and annoyingly disparage the Gini coefficient, our best quantitative measure of inequality); universal free health care; universal free preschool and public higher education; equal per-pupil expenditures in primary and secondary school; a Universal Basic Income (maybe); enforcement of labor law (the nonenforcement of which has destroyed American unionism); enforcement of tax law (the nonenforcement of which is a trillion-dollar annual gift to the wealthy); all adult citizens automatically registered to vote; exclusively public funding of elections; transparency mechanisms, including a vastly expanded Freedom of Information Act; and accountability mechanisms, including recall, at all levels. If that’s not an egalitarian program, why not? And if Graeber and Wengrow wouldn’t regard it as well worth fighting for, why not?

I think I know why: Because, unlike in grubby, soulless social democracy, people in true communism (for example, the indigenous societies of the Northeast Woodlands before the European invasion) “guaranteed one another the means to an autonomous life—or at least ensured no man or woman was subordinated to any other.” That is the anarchist ideal. Well, what is the purpose of the socialist/social democratic reforms I just proposed except to guarantee everyone “the means to an autonomous life” in an industrial society? “Industrial society”—there’s the rub. Is anarchism feasible in a society of any considerable size or complexity, where coordination, authority, and expertise are essential? How much of mass production, technological innovation, cheap paperbacks and CDs, and the rest of our accursedly seductive late-capitalist way of life do we want to walk back? And how do we do that without starving or stranding or inciting to rebellion the hundreds of millions of hapless humans trapped into dependence on cars, air travel, supermarkets, and single-family houses? Few contemporary anarchist writers have addressed these questions squarely, and none satisfactorily.

Still, socialists and social democrats have a very large blind spot of our own: the ideology of progress. Believing that democracy and technology advance together, that representative institutions and scientific rationality will reliably and permanently vanquish ignorance and want, and that the historical record demonstrates all this, we can’t account for historical regression (like contemporary right-wing populism in Europe and the United States) or precocity—outstanding political virtue or imagination among peoples with few material attainments. Anarchists, free of this intellectual baggage, need not tie themselves in knots to explain these “paradoxes” of progress.

Labels, clearly, are an aid to misunderstanding. Surely it is not necessary to choose between freedom and equality, much less to disparage those who make the opposite choice. If an anarchist believes in freedom, and a socialist believes in equality, what is someone who believes in freedom and equality? A wise person and a useful citizen.

sábado, 22 de mayo de 2021

Spain ‘at War’: Strategic dispute against Morocco over Saharawi Blood Phosphates

By Pablo Heraklio Published KAOS Source La Tarcoteca 4.5.2021 translation thefreeonline

Juan Carlos I will go down in the Annals of History as one of the worst and most abject monarchs of an era. He killed his brother, took his father away from the crown, was involved in the death of his cousin, plotted several coups in his country, many others abroad, orchestrated the GAL [1] (state sponsored death squads) together with military groups, decorated all the Dictators he could [2], also torturers and murderers, trafficked in arms and used his position to defraud his personal fortune, doing more service to Switzerland than to Spain.

He let us enjoy a wonderful state infested with fascists in the high military, police, judicial, political and business commanders, where war criminals went unpunished and were amnestied without trial; avoiding the recognition or compensation of the victims [Amnesty Law 1977 (3)].

|

This infestation became the current ruling oligarchy, which was later joined by representatives of the various international corporations.

But that was not the worst at all. His narrow-mindedness and personal greed place the Spanish oligarchies in the midst of an international conflict that is getting bigger and bigger every day.

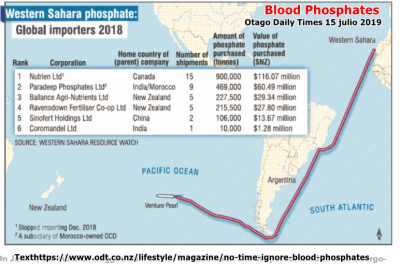

45 years ago Juan Carlos I « Swap the former colony in exchange for being able to keep the crown – canarias-semanal. [4]» 2021. Now Spain is involved in the Sahara War for control of the Blood Phosphates.In Morocco [5]a geopolitical conflict is underway for global food security, as important as the control of oil reserves. Maybe more.

“Three countries, China, the United States and Morocco control 67% of the world phosphates total, with Morocco 15%” – Ecología Política [6] Political Ecology 2012. Part of the phosphates exploited by both Morocco and the USA are plundered from Western Sahara.

The dust of these lands naturally fertilizes large areas of the planet, other continents, from the Amazon to Europe or Africa. The concentrated salts of fertilizers pollute aquifers and land, generating wastelands, dead water, and requiring constant chemical rectification. Thus, the very functionality of global ecosystems is also at stake.

International Military Conflict

A conflict no longer commercial, but open military; but silenced by what have already been called Blood Phosphates, started on Nov 4, 2020 with the declaration of the State of War of the Polisario Front [7].

In this war we are seeing actors like the USA, France, Israel, China or Spain pushing political and military pressure. Beyond gas and oil is the business of world fertilizers, potash, phosphates, nitrogen compounds in Saharawi lands.

Behind the fertilizers is the entire transnational agrochemical industry [8], the Big-Agro: Cargill, Monsanto, Nutrien, Northwach, Paradeep Phosphates, Ballance-Agrinutriens.

Sahrawi sands are transported around the world and treated in a thousand ways to obtain the fertilizers that are consumed by intensive agriculture from Murcia, Huelva, Castilla y León or Aragon to Nigeria, New Zealand, Australia, Egypt, India or China, affecting thus to the food security of these countries, and hence its geopolitical importance …

The size of the contest

This is the size of the contest, that the USA has sent its Sixth Fleet.

It has taken the Canary Islands as a control point for exports from the Mediterranean and North Africa. It is already maneuvering and showing his mastery of the area:

“Some maneuvers by the US affect air traffic with the Canary Islands – Canarias” 3.3.2021 [9]

«Threat from the United States and Morocco to Spain- Voltairenet.org» 16.3.2021 [10]

They knew something.

Since 2012 it has used the Canary Islands as its western drinking trough:

“The Island [las Palmas] will serve as a logistics base for the United States and its allies to intervene in the Sahel – La Provincia” 2012 [12]

To close the southern clamp they plan to control the area with the building of a new base to the south of the area:

«Competition heats up for NATO Sahel compound contract – 04/07/2021 – Intelligence Online» 2021 [13]

France maintains a large contingent to the east in Mali, central Sahara desert, to ensure control over the uranium mines, fertilizers and the northern Sahel, despite popular protests.

“France’s Impressive Military Deployment: More than 30,000 Military in Five” Spheres “of Influence” 21.1.2021 [14]

Morocco has been a faithful ally of the United States since the times of Hasan II and provides american corporations with natural resources plundered from their own people and from the Saharawi. It is both an ally and a competitor of Spain:

«Morocco offers the US a base to close Rota: Mohamed VI gives facilities to the Americans» 2020 [15]

At this stage of the war, Spain provides arms to both Morocco and the Polisario Front while negotiating with Mohamed IV [actual king and ruler] the future of the companies that will exploit potash and phosphates. Everything in its place:

“Spain declared war on the Saharawis by selling and giving arms to Morocco in full offensive in Western Sahara” 3.5.2021 [16]

Russia is not so affected since its agriculture is extensive and moves towards its Siberian districts. China is an interested party, but for now it does not seem to speak, although sooner or later it will be affected. Everyone has a plan.

Transnational extractivism, the new Colonialism

The interests of Spain are very clear:

«The ships and companies that plunder the phosphates of the Western Sahara occupied by Morocco>> Sahara Press Service 2018 [17] and «“Spanish companies exploit the riches of Western Sahara – eitb.eus” 11.18.2021 [18]

They represent European interests and stand against Moroccan interests; and of the Sahrawis.

As you can see, the damn Ibex35 [spanish stock market] is the hand that rocks the cradle. Here are some infamous protagonists: Abengoa / Javier Benjumea, Acciona / JM Entrecanales, Gamesa-Siemems / Andreas Nauen. Although also others less known as FMC Foret/ Mark Douglas-Javier Carratalá, Jealsa / Elena Chamorro, EuroPacífico, Granintra / Luis Jimenez Chirino, IsoFotón / Carlos Zambudio Jimenez, Ership / Gonzalo Alvargonzalez Figaredo, NETMAR / Ángel Riva Fierro, Meripul / Conrado Merino Inyesto or Troulo among many others.

Construction, fishing, energy, agrochemical; and military: Expal (explosives) / Jose Luis Urcelay Verdugo, MAXAM (explosives) / Urcelay himself with Juan Carlos García Lujan, Instalaza / Leoncio Muñoz BuenoMBDA (missiles) / Eric Beranger, SAPA (artillery) / José María Berasategui Liceaga , Indra (electromechanical) / Fernando Abril-Martorell .

All of them share a set of crossed interests far beyond the monetary, strategically, since the control of trade in the area and access to low-priced food that interests countries such as Germany, France or the USA is at stake. .

Not separately, but together and under pressure from third parties they are capable of moving the Spanish state machinery to force a deployment of military forces in the area.

Silent conflict, Spain in a proxy war

This colonizing process in Spain was called the Empire and the decolonizing Decadence of the Empire. This new recolonizing movement will be called Disaster.

The interests of Spain, of its oligarchies, are once again trans-Mediterranean and open conflicts are envisioned with the sending of troops in the medium-long term.

Spain, the exploiting businessmen, yearn for phosphates, at the strategic mandate of the European powers, whose access was cut off due to the puerile Rogue Maneuver.

If the Sahara had been duly decolonized, Spanish companies would calmly exploit those resources and get a great geostrategic prize, maintaining a defensive and containment stance against Morocco.

Which would have given him access to other types of contracts and perks, such as exchanges for fishing, agricultural or hydrocarbon quotas. An Ace in international negotiations.

The loss was not only billion dollar, it was strategic, comparable to losing the Strait of Gibraltar. This can be understood by even the most fanatical fascists [supporters of the king, who make the deal with Hasan II].

Too much power for one person. Due to the clumsy and greedy maneuver of the robber Bourbon, the Spanish oligarchies, representatives of international powers interested in the fight - just look at the composition of their directors boards -, they come themselves into conflict with Morocco; with the USA rolling as the referee.

Now they have to adopt an offensive posture instead, which implies strain and depletion; decrease in profits and assumption of losses of all kinds.

For this they need military support and justify interventionism:

–Arm both Morocco and the Arab Republic of the Democratic Sahara SADR,

–Promote

conflict and mutual aggression. At first, the objective is to contain

the conflict in the two countries but maintaining the threat of an

extension to the neighboring countries.

–Training squads to interrupt the exploitation of resources, threatening to force the intervention of third parties; meaning EU-NATO.

Spain delivers armaments to Morocco, a poisoned gift. Spain will provide arms in exchange for commodities and money, bleeding both adversaries. For this, it is essential to increase the tension between the fighters; which usually involves attacks in both countries, possibly using some fraction of Al-Qaeda / Stay Behind network.

This rearmament will be strategically counterproductive in the future. But who cares, if by now the quarterly balance works out.

Spain, the breadbasket of Europe, has the support of the EU, and when the time comes it will play its card with NATO, which gives it an advantage.

If this war has not transcended to the public, it is on the one hand due to the media lock, since the same companies that invest and finance the mass media are those that invest and finance the Agrochemicals and plunder companies mentioned above: armed banks [19] such as BBVA, Santander Bank, LaCaixa Bank; the own Ministry of Defense of Spain; international investment, hedge and venture capital funds such as Black Rock, Vanguard, Capital, JP Morgan, Berkshire Hathaway.

And the policy of professionalized recruitment, which transforms the state army into a mercenary army at the service of these oligarchies; that covers any military intervention with a cloak of opacity and impunity. We are in the silent conflict phase.When will we see an open conflict?

In other words, how is a casus belli generated? Attacks and terrorism. How is a war morally fueled? Fascism. The rise of fascism in Spain [20], France, Italy, Germany, is not accidental. This Recolonial situation did not occur in the decades of the 80s or 90s.

The conflict that today is in its initial phases will worsen; we do not know the specific terms and times. But we can intuit how it will happen: All wars have three phases: pre-war or preparatory, confrontation or operational, and post-war or outcome. The first one already has happened and we didn’t even know about it.

Since war was declared by the Polisarian Front we are in the operational phase and we can expect several events:

1-We know that right now the government of Pedro Sánchez is involved in the preparatory phase of supplying arms to both parties. This escalation is essential. Fait Accompli.

2-As we have seen in Syria, Libya, Yemen or Iraq, the intervention of the powers is limited to air and maritime control, while land operations are delegated to local militias/ irregular armies. The conflict can continue set like this for years, allowing a comfortable plundering of resources.

-The next intervention would be the sending of training commands and training of military cadres that promote war operations between both countries. Surely they are already underway in the various academies and training camps.

-Then after air and customs control; a phase in which the United States has already entered and which will accompany Spain from Rota and Las Palmas. Developing.

It should be followed by the increase in skirmishes and military assaults in the SADR. Later in Morocco and Mauritania. Finally in Europe. The worst geostrategic decision, a door for Popular Revolution.

3-The milestone will be the leap to public opinion. Possibly the first attack in Spain, either under a false flag or a real one, or against Spanish interests abroad.

When it happens, all the corporate media will vomit their usual infoxication in unison.

This will be the signal to authorize direct intervention. This could be the worst geostrategic decision made by the Spanish oligarchy since the Sahara Exchange.

It will coincide with a period of internal instability/ ecological transition that we are already experiencing due to the accumulation of crises to which would be added the diversion of funds to the military. It would fill the barracks and factories of impoverished people; and flowers at cemeteries. Reigning fascism.

Finally, the hard repression of the protests that arose against would arrive, posing scenarios more similar to those of the Melilla War of 1909 than to those of No-to-Iraq War in 2004 [wide spread riots instead of pacific prostest].

It will be the moment of disaster, because It will mean not a government, but a domination of fascism as we have not seen since the days of Franco’s raids. The burning, volatilization, of resources would suppose the gradual dysfunctionality of the State, with all that this implies.

Let’s hope we’re wrong, but the scenario is very possible; the national oligarchies are very scared. The Germans too. The crown of Juan Carlos will cost Felipe VI many more deaths. Will he hold on?

From an objective point of view, the Sahara War is part of the struggles to maintain the Capitalist-Oil system, characterized by: cheap energy, centralization of production, intensivism and industry on a world scale.

In the new context of shortage of high-density energy, hydrocarbons and plastics -peak of oil- Capitalism-Post covid19, it will mean that the less energy for transport will reduce the intensity of the production and distribution of goods.

This push for a decentralization of production, including food, and de-scaling of industry; deglobalization and the creation of new economic blocks. The importance of the world’s phosphates may have a peak, but it will diminish in the long run, and a military adventure would only serve to waste resources that would otherwise be used for a much more lucrative rearrangement.

But of course, this decentralization supposes a net loss of power, to which the aforementioned companies and governments are not willing. We are seeing the last throes of an old system that breaks down, and in a big way.

The reality is stubborn, the more they insist on their military adventures, the faster their fall will be, because the faster they will lose supports, burn their resources and increase internal resistance to the putrescent regime; and sooner we will approach to our revolutionary moment. [21]

They won’t stop until they destroy the planet.

_____Notes

[1] https://diario16.com/juan-carlos-i-fue-el-primero-que-tuvo-en-sus-manos-el-acta-fundacional-de-los-gal/

[2] https://www.publico.es/politica/espana-revisado-condecoraciones-dictadores-entregadas-juan-carlos-i.html